Creativity Secures People’s Voice on Women Trafficking under Censorship

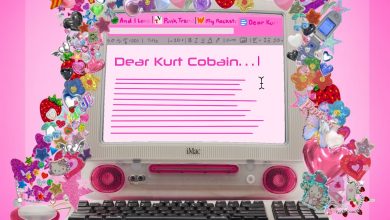

Source: “This World Abandoned Me” by @Jorsin- and @revos_one on Weibo on March 5, 2022

Image description: A photograph of graffiti depicting a portrait of Xiao Hua Mei. Her face, neck, and shoulders are outlined in black and white on a red background. The caption reads “This world abandoned me.” The black and white characters scattered throughout the right side of the portrait read “Liberty, Civilization, Equality,” sarcastically referring to the values promoted by the government.

CW: human trafficking, gender based violence

The public in China has been infuriated by a video that was posted in January 2022 that shows a woman chained by the neck to a doorless hut in Feng County, a rural area in East China. The woman, called Xiao Hua Mei (Little Plum Blossom), has been apparently imprisoned by the man she married and has eight children with. The official investigation eventually pointed out that the woman was trafficked to him, yet, people’s outrage persisted as a series of reports remained inconsistent and were deliberately kept ambiguous. While discussions about trafficking women are systematically censored and evidence of interpellations deleted, many Chinese citizens find innovative ways around internet censorship and create new systems of communication, which involve homonyms, sarcastic works of art, and reinterpretation of traditional culture, to secure their conversation and resistance.

There has been an endless stream of deletions of posts and social media accounts, and even the cancellation of a person. After boldly criticizing Chinese president Xi Jinping as a “human trafficker” on a YouTube chat show, the well-renowned female Chinese American author Geling Yan completely disappeared from Chinese social media. What is erased altogether is her Weibo (the Chinese version of Twitter) account, as well as “Mother, oh, Mother!,” the piece she wrote in response to the video referenced above.

The Weibo user Wuyi was charged with disturbing public order and detained by local police after she visited the village Xiao Hua Mei was living in, attempted to get in touch with the woman, and managed to obtain considerable attention on Weibo. Exacerbation of online censorship ensued, affecting ordinary netizens who were identified by the government propaganda sector as outspoken in this issue: people have reluctantly acquainted themselves with sudden and unwarranted deletion of their Weibo or WeChat accounts.

The Chinese public’s determination to preserve the fading realm for expression and to see the Xiao Hua Mei case justly settled is unfathomable. Their resilience prompts unending creativity. “Chinese internet users have devised an array of creative ways to navigate around government censorship of China’s cyberspace,” said CNN’s Hong Kong correspondent Kristie Lu Stout.

A new lexicon has been developed by Chinese netizens who have wittily replaced words and phrases that are directly blocked, with superficially unrelated yet rhetorical expressions. In the comment page of the CCTV Weibo account, many netizens liken incompetent legislation and law enforcement to a “broken fishnet” and a “torn umbrella,” indicating their failure to arrest human traffickers and to protect disadvantaged groups. The event is compared to situations in which a broken fishnet cannot catch fish, and a torn umbrella cannot shelter people from the rain. Since the village is sealed off from any visitors and its name is banned on the internet, it is referred to as an “iron bucket” — like a bucket, people are suffocating and no light can penetrate.

Since direct discussion about chains and government failure is usually censored, the chain, as a symbol of resistance and truth-seeking, has been widely incorporated into pictures and memes. In an image that went viral, the iron lock attached to the chain around Xiao Hua Mei’s neck is now depicted as blood-red, and this is easily and tacitly apprehended by internet users, who habitually use the color red to refer to the Chinese Communist government and implicate systematic political violence.

Despite the plight underlying it, the image of chain has been imbued with sarcastic aspiration. To celebrate International Women’s Day on March 8th, netizens kept reposting pictures in which the date “8” is portrayed as a knot of chains or the chain is cut by an iron female sign. Although politically sarcastic performance art is often bombarded with official disapproval, it garners the support and warmness from internet users. On the same day, three women tied themselves with chains and walked around Downtown Shanghai. Their deed was enthusiastically extolled and their pictures were widely spread.

Through the regeneration and reinterpretation of negative elements, Chinese netizens have weaponized the blocked words or imagery initially politicized by the authority — censorship is now instrumentalized to counter itself, and is thus proved futile. Basing the source of inspiration on censorship and oppressive policies, the netizens resiliently manage to secure their communication with a system of euphemistic speech.

Historical works are references for netizens as well. In an interview on creativity in China, Sean Leow, the founder of Asia Society, a website that serves as a social network for creative young people in China, discusses neo-traditionalism, which I see as a strategy of those who navigate around internet censorship. “‘Neo-traditionalism’ is the reinterpretation of traditional Chinese imagery, stories and influences, often combined with modern styles,” he said.

Two competing forces of interpretation are derived from neo-traditionalist perspectives. On one hand, the governmental propaganda system, by censoring non-conforming opinions and associating itself with long-standing values, endeavors to hegemonize traditional cultures and generate political legitimation. On the other hand, the netizens contrast the wretchedness of Xiao Hua Mei with a multitude of much-loved traditional images or characters.

The Chinese word “xi” (喜), which means “bliss” and “ecstasy,” is usually used for decoration in traditional Chinese weddings and printed on 20th century marriage certificates as a symbol of official congratulation to the couple. The “xi” printed on Xiao Hua Mei’s marriage certificate looks ironic, since the marriage is cunningly masked to be a mutually consented one. Hence, people start to see it as an oppressive character that, just like the tangible chain, is a systemic, unshakeable fetter. Based on that, artist Xinmei Liu painted a picture that quickly turned popular among netizens — in the picture, “xi” stretches and hogties the chained woman.

Netizens have also rewritten famous episodes of Peking Opera to demonstrate that the unjust cases in old despotism can surprisingly fit into today’s Chinese society. In the piece Su San Qi Jie, Su San is trafficked multiple times since she was a young girl, and eventually became a concubine of a businessman in Hongtong County, Shanxi Province. Frustrated by the corruption and unresponsiveness of the county government, Su San exclaims, “There is no just man in Hongtong County!” People found that if Su San is replaced with Xiao Hua Mei, and Hongtong County is replaced with the county where the chained woman is in, the plot still applies to today’s context.

Through the creative derivation of and active adaptation to censorship, netizens generate enormous power which attests to their resilience and determination. Not only are they inspired by each other, but more importantly, they show the transformation of tools of resistance, which work to render the censorship useless.