Observations from the Psych Ward

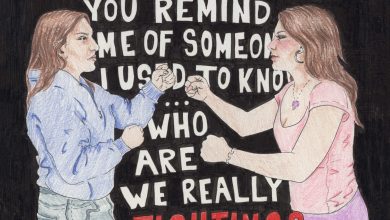

Design by Shannon Boland

Being in the psych ward is a decidedly unhumorous situation, but I find myself constantly amused. So much in the ward is taken at face value. I always feel like I am part of an inside joke with myself.

I eat countless packs of saltines. They are kept in a locked drawer labeled “crackers.” Each time I want one I have to ask the attending nurse to unlock the cracker drawer, please.

I spend most of my time sitting on the hard teal couch, journal and pen in hand. I fancy myself a mysterious artist, and maybe I appear so to the other patients. What is she thinking? What is she drawing? I wish I had a beret or some funky pants. Mostly I just sketch chairs and the backs of people’s heads.

I sit cross-legged; I splay my legs out; I crouch on top of chairs like L in Death Note. I sit super gay. I have never been so comfortable sitting so gay.

I learn that it is possible to mess up chicken noodle soup. Later I request a baked potato and it is divine.

One day we have a therapy group called “self care.” I see this on our schedule and it is both extremely funny and deeply sad. I think about the term self care, whether it can possibly hold any residual meaning after being sucked dry by Instagram influencers and Buzzfeed product ads posing as articles. I wonder if the occupational therapists running the group register any irony in their encouragement of “self care” while we are confined in institutions that strip us of bodily autonomy, subject us to round-the-clock surveillance, and keep us under the constant looming threat of seclusion and restraint. I tell myself it is not the occupational therapists who have confined us, and in the end I have to admit that it feels nice to soak my feet in warm water. Maybe this is just a rationalization. Maybe a rationalization is all I can hope for in here.

I stare at the serenity prayer posted on the wall, so commonplace in psychiatric or therapeutic settings: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.” I think about modern psychiatry as a capitalist venture, one that promotes tolerance of intolerable conditions. Mark Fisher criticized in “Capitalist Realism” what he called the “chemico-biologization of mental illness”— the treatment of mental illness as a personal and biological pathology instead of a reaction to increasingly distressing social conditions brought on by the rise of neoliberal capitalism. In this context, the prayer is troubling. Who determines what parts of our world we are able to change? Are we to accept oppressive power structures with serenity?

I decide that 10 a.m. is too early in the day to be thinking about neoliberal capitalism, so I shelve this internal discussion for until at least after lunch. I take a break with more saltines.

Another sign reads: “For every disciplined effort there is a multiple reward.” Is this yet another example of neoliberal propaganda that depoliticizes mental illness and suggests that we can will ourselves out of disorder, an insulting neglect of the socioeconomic factors that lead to mental distress? Or is this an affirming reminder of personal agency for patients who frequently feel powerless? And what of the fact that the psychiatric institution itself is often what makes the patient feel powerless?

I don’t think my treatment team would be too enthusiastic about my musings on critical psychiatry. I keep those thoughts to myself during our meetings.

To their credit, my treatment team is very kind to me. This is not always the case at psychiatric hospitals, even as a soft-spoken, articulate individual who attends a prestigious university and speaks with no discernible “foreign” accent. Multiple practitioners remark on my insight, my so-called intelligence. I am truly a model patient, the most normal crazy person a doctor could hope for. I wonder how patients with more stigmatized symptoms — “scary” or “aggressive” behavior, heavily compounded if they are Black and already cast as more threatening — or those who are unable to advocate for themselves in an “educated” manner are able to navigate mental health institutions.

I reflect on a class I took at UCLA several quarters ago called Sociology of Mental Illness. The course illuminated many of the racist, misogynistic, ableist underpinnings of not only the modern psychiatric system but the construction of “mental illness” itself. I read about the long history of institutionalizing political dissidents under the guise of psychiatric care. I learned about “protest psychosis,” a supposed mental illness coined in the 1960s to describe the so-called “nationalistic fervor” of Black Americans in the Civil Rights Movement. I began to develop a sociological framework of mental illness as a socially constructed system of classification that pathologizes and punishes social deviance. But I struggled (and continue to struggle) to reconcile much of what I learned in that class with my personal experience of mental illness.

In no other area of my life is there such a gap between theory and lived experience. My understanding of mental illness is rife with contradiction. I can write essays about mental illness as a sociopolitical construction, but when I am in the depths of my own distress it feels so deeply personal.

How do I criticize the massive pharmaceutical industry without acting like the people who have shamed me for taking my meds? Is it irresponsible to oppose institutionalization when there is presently no widespread viable alternative? Is there a viable alternative? Am I a hopelessly reformist liberal for seeking comfort in institutionalized clinical mental healthcare or a hypocrite for criticizing it all the same?

Ultimately, I am not in the psych ward to find all the answers to my questions, and certainly not to work out a cohesive radical theoretical approach to mental illness. I leave unsure, reckoning with many of the same questions as when I was admitted.

One therapist allows me to bring home a cutting of Thai basil from the hospital garden. I resolve to plant it in soil when I return home and try to start my own garden. I forget to bring the basil with me when I am discharged — I had left it in the common room because my roommate was having a crying spell in our room and I did not want to disturb her. I avoid the common room when I am leaving. I feel guilty that I get to leave when they don’t.

Assorted Observations:

There is a piano at the hospital, so after the first day I ask all my visitors to bring me sheet music. I learn later that my mom drove to the Century City mall and then to a piano store just to find me music to play. She ends up buying not one, but two books of sheet music. I am struck by the (not uncommon, but always staggering) realization that I do not deserve my mom.

I talk with the other patients. There is not much to do throughout the day but talk. We share our fears, our trauma. I learn so much about my roommate, but I don’t even know her last name. She is in my life for less than a week, and I might never see her again.

I attend a karaoke group on the floor. We sing “Girls Just Want to Have Fun.” The nurse leading the session is intent on verifying Cyndi Lauper’s thesis, and he asks the girls in the group one by one if we really just want to have fun. Do I? I admit that I do frequently just want to have fun.

My friends bring me my watercolor palette. During a break I sit in my room, painting a sunset, singing softly to myself, and it occurs to me that if I were home I might be doing the exact same thing. I still have to ask a nurse to unlock the bathroom every time I need to pee, though.