Pick-Me Girls: Feminism’s Phony Villains

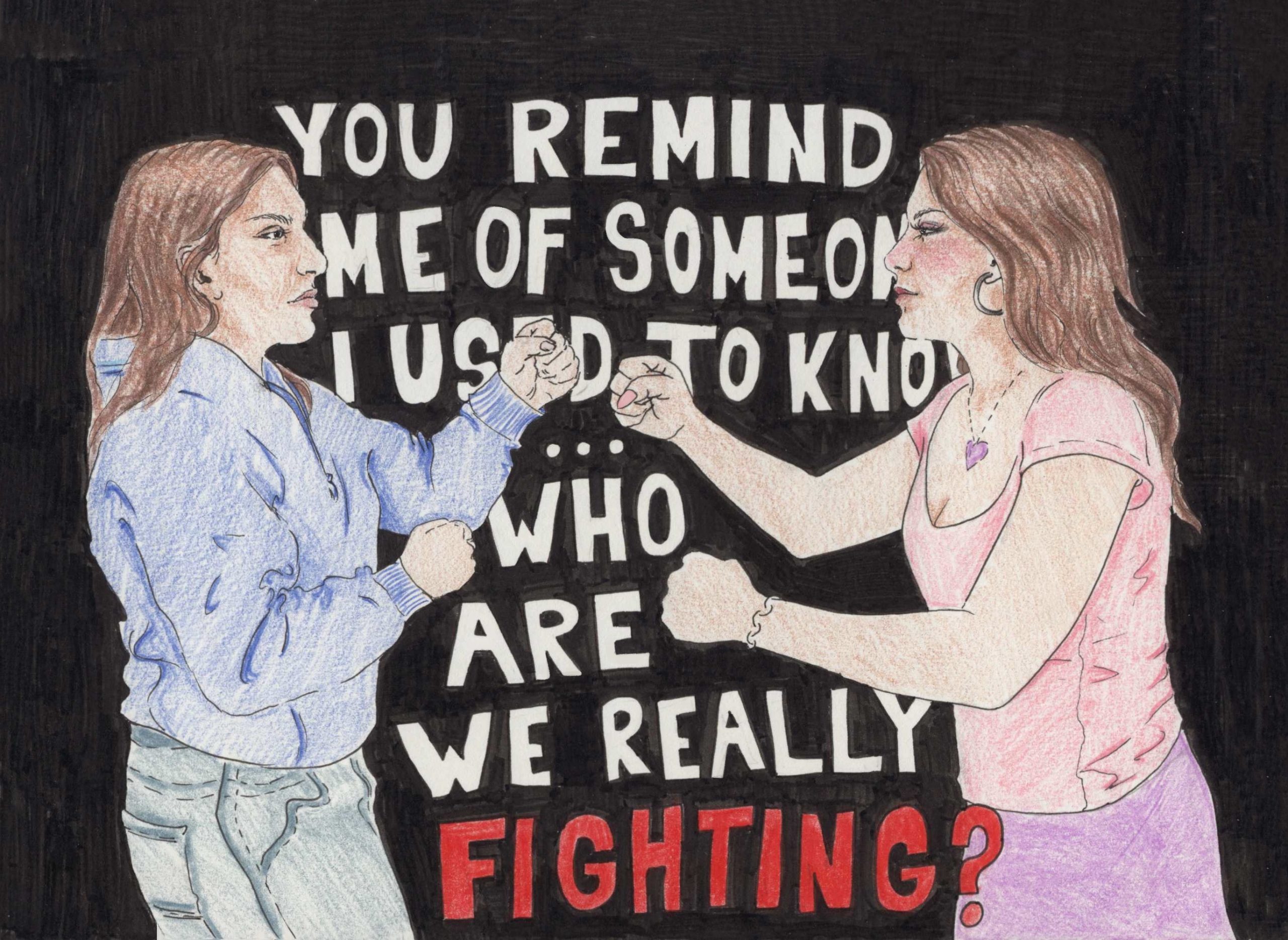

Image Description: Color pencil drawing of two girls fighting each other, one in a pink shirt, purple skirt and jewelry and the other in a blue hoodie and gray jeans. Against a black background and behind the figures the words “YOU REMIND ME OF SOMEONE I USED TO KNOW… WHO ARE WE REALLY FIGHTING?”

Design by Justine Charroux

Oh, the Pick-Me Girl. There’s just something about her that makes her a little more special than your average woman. She’d never spend an afternoon in an Ulta, she doesn’t need to, she’s a natural beauty. And no, she can’t go out tonight, she’s watching The Game. It doesn’t matter if it’s her team or not. The Game is always on. Walk away, vodka-cran, cause for the Pick-Me Girl there’s nothing that could come close to cracking open a few cans of Keystone Light with the boys of Alpha Sigma.

So goes the legend of the Pick-Me Girl, the internet’s favorite witch to hunt for the last few years. She’s been accused of sowing division between women and of being one of the biggest hindrances to female solidarity — but why? Is she truly a smug villain in the story of feminist history, or just a misunderstood scapegoat being used to gloss over far greater threats to bonds between women?

Let’s start with the basics: what is a Pick-Me Girl? The term was made popular by Black women, particularly on Twitter, and appropriated into larger online circles where it was eventually given its now broadly-understood meaning: a woman who belittles or derides other women in order to gain the attention of men.

That last part is important — Pick-Me Girl was initially a legitimate critique of internalized misogyny. Feminists recognized that solidarity was crucial for the women’s liberation movement. This is of course because there is strength in numbers, but also because men have always had a vested interest in dividing and conquering when it comes to feminism — the more women that “defect” from the feminist cause, the more men can undermine the feminist cause as something necessary for women’s happiness. Thus, the Pick-Me Girl discarding solidarity with other women was originally seen as a flippant concession to the patriarchy. The term calls out women who criticize other women with the sole purpose of gaining favor with men, behavior that only serves to uphold the patriarchal notion that women’s relationships to each other are inherently inferior to their relationships to men. The notorious quote associated with all Pick-Mes is that they’re “not like other girls,” the insinuation being that it’s offensive to be seen as “like other girls.”

So the Pick-Me Girl quickly became the villain of internet feminist discourse as the person who turns her nose up at solidarity so that she’ll be liked by misogynist men. As the term gained popularity, the Pick-Me became framed in opposition to her beloved foil, the Girl’s Girl, an archetype of woman that would be caught dead before she let a man get between her and her #girlsquad. These two archetypes seemed to be reflective of the collective understanding about what behavior is acceptable. We respect it when women support each other and prioritize their relationships with each other, and we take issue when they bring each other down so that men will like them. OK, sure, I’m with you. Nothing seems inherently terrible about this yet.

But of course, we can’t have nice things for too long. Since its inception, the term has been flattened and defanged, turned into nothing but a new kind of misogyny with the kind of frightening speed that only the internet can provide. When I was 14 or 15 and first becoming aware of what the term meant, a recurring example I saw of the Pick-Me Girl went something like this: Oh, I’m not like those girls who wear tons of makeup to school every day. I prefer to go all natural.

That’s unnecessary, yes, and even rude. But still, it’s telling that the oft-repeated stereotype of the Pick-Me Girl is that she’s the one who’s outspoken about how she doesn’t wear makeup — as though the choice to wear makeup is just a “girl thing” instead of a decision heavily impacted by the beauty industry’s predatory tactics of creating constant profit from a primary audience of women through engineering and then capitalizing on their insecurities. It’s alarming that comebacks to the Pick-Me Girl often accuse her of jealousy or suggest that she must harbor some deep insecurity over not being “woman enough.” It becomes downright hypocritical when these skits “put the Pick-Me Girl in her place” through the rejection of male attention … the very thing that the original usage of the term intended to devalue.

The criticism isn’t novel anymore, either. There are compilations on compilations on YouTube essays and even entire TikTok accounts that have garnered viral fame from doing the same, reductive skit over, and over, and over again about the Pick-Me Girl. We handed the internet a caricature of a woman who it can make fun of without picking up allegations of sexism. It’s feminist, even, to ruthlessly belittle this kind of woman as long as we make it very clear — it’s because she’s a Pick-Me Girl! See! She’s the real misogynist! Not us!

It seems like being a Pick-Me Girl is one of the ultimate threats to women’s liberation, yet simultaneously the term is often used as shorthand for any woman the internet suspects of doing things that aren’t Girl’s Girl-y. This raises two questions.

#1: If we take the current discourse around Pick-Me Girls and Girl’s Girls entirely at face value, which I don’t, it still begs the question: Is it really OK to alienate and mock girls who we have decided are dealing with internalized misogyny? Can we justify that just because it’s “in the name of feminism?”

#2: How much of the current circular Pick-Me Girl discourse has just become a “feminist” way to regurgitate the most base levels of misogyny? The term has lost its original meaning and is now just a blanket insult to target women who do anything that fall outside conventions of femininity. As Aubrie Cole put it for the Daily Trojan, “You don’t need to be a blatant anti-feminist to get called a pick-me girl, you can simply play video games!”

I’m hardly the first to point out that the recent popularity of the Pick-Me Girl is a misogynistic trend in and of itself. Cultural critics, students, and psychologists alike have all called into question the way the trend only serves to amplify existing sexist attitudes. Many voices have piped up in recent years to critique the way the insult is lobbied at any woman who’s perceived of transgressions against her gender, without any question of exactly who is being given the power to define womanhood or the values enshrined within that definition. In most of the cases today, men are strangely removed from the equation — instead, the women targeted the most for offenses against their own gender seem to just be women who defy modern conventions of femininity.

It’s unfair to view a Pick-Me Girl as a one-dimensional villain and not also recognize the way she, too, is a victim of the patriarchy. On a certain level, internalized misogyny is just a form of self-hatred, cultivated by a society that conditions women to look down on themselves — and that shouldn’t be dealt with through shame. Isolation and insults will not be any sort of balm for a misguided young woman who has already decided she doesn’t get along with other women. Most of the people with pick-me syndrome tend to be teenage girls working through the onerous and terrifying task of developing their own identity. Maybe they have a flawed way of going about it, but we should be meeting them with empathy, understanding, and education.

The other side of the coin is that many now lean heavily into applauding themselves and others who express their gender through traditional means. As a counteraction to the growing disdain of the Pick-Me’s gender norm rejection, other women show off their comparative virtue by proclaiming themselves to be Girl’s Girls and leaning into the hyperfeminine, celebrating themselves as Good Women based on their passions for style, makeup, gossip, and all things considered ‘girly’.

More concerning than the Pick-Me Girl trend is the reaction to it. Only a few dominoes need to fall before we start rapidly toppling ourselves backwards into gender essentialism. By painting women who fall outside our bounds of traditional gender roles as the villains, we inherently create a dynamic where the feminine-presenting women are victims. Not of the patriarchy, which would be true, but of so-called Not-Girl’s-Girls. Rallying cries to “let women be feminine” come from self-declared advocates for women, without any apparent realization of how these calls are eerily similar to the outspoken conservative goal to “preserve femininity.”

The urgency with which people argue women should be ‘allowed’ to be feminine is particularly confusing. There is an implied victim in the statement (the feminine woman), but no apparent attacker — it’s never clear which institution with any power is preventing women from expressing traditional femininity. Most of them encourage it. Women deviating from the norm are socially punished under suspicion of trying to take up a space they don’t belong in. With trans children under attack, abortion rights regressing, and talk about sexuality and gender banned from classrooms, it should come as no surprise that the goal of hegemonic society right now is to reinforce cissexist gender roles that prevent women and other minorities from reaching the same heights as their heterosexual cisgender counterparts.

There’s some collective delusion being experienced where women are shunned for being too feminine, wanting to be stay-at-home moms, or generally liking “girly” things. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Women face immense social pressure to look beautiful. The pursuit of acceptable beauty comes at the cost of our time and money, spent on treatments and makeup to perpetually meet this ideal across our work and home lives. Women who choose to ignore this expectation face consequences, which could range from negative perception to termination of employment. There is hardly booming support for women entering professional spaces. Professional women’s athletes are still struggling to receive equal treatment and wages to their male counterparts, and women in traditionally male-dominated fields are almost always fighting discrimination and harassment. Despite now entering the workforce at a higher rate, women in heterosexual marriages still take on the majority of the housework and child-rearing responsibilities since the assumption persists that the domestic sphere is primarily a woman’s realm. Taken together, this is a clear pattern of women being denied adequate support when taking on male-dominated roles and facing a push urging them back into the feminine spaces of beauty and domesticity “where they belong.”

With all evidence of discrimination to the contrary, there’s no good reason for anyone to act like traditionally feminine women with a love for beauty, housework, and Girl Things ™ are some endangered species on the cusp of extinction. The lived reality of many women is a social and economic pressure to be feminine. Women who choose to step out of line are met with resistance — both from traditional conservatives but now from the so-called feminist left as well.

Nothing is inherently subversive about femininity. I’m a relatively feminine woman but I can understand that conforming to gender roles the way I do actively helps me — it helps me be taken seriously and it legitimizes me to the gatekeepers of institutional power, who are frequently men. To act as though my compulsion of carrying out performed femininity as survival instinct is a virtue to defend, rather than a flawed ideology to deconstruct and get rid of, is insulting.

This is why it’s so frustrating when people start to uncritically enshrine certain values, experiences, or worse — things, as the true markers of being a Girl’s Girl. I struggle to figure out when or how criticizing Taylor Swift became a feminist faux-pas, or why feeling a disconnect with the Barbie movie is a red flag. Who are the gatekeepers of girlhood? Why do we accept the same definition of it that someone’s out-of-touch grandfather might give? And most importantly — who do we leave out when we define girlhood this way?

At times like this, I think of a video I saw posted frequently by the sororities at my university before they started recruitment last summer. Over a then-trending audio from Barbie over Billie Eilish’s lamenting vocals, they would weave together a montage of all their members hanging out together at their events or parties, with the single word “girlhood” written in Arial font right over it.

The irony wasn’t lost on me of a notoriously exclusive, class-prohibitive institution with high expectations for their members to be a certain capital-T Type of girl, posting a video about what being a woman looks like. The videos very earnestly lay claim to a “feminist” audio proclaiming some universal experience and bond of girlhood over a montage of date parties, rush events, and hot yoga classes. And sure, a single video is “not that deep,” and I’ll admit that capitalizing on a trend to increase recruitment turnout is hardly a novel thing for any organization to do, but I use this example because sororities are a great metaphor for the inherent flaw in trying to define girlhood as a universal experience. They’re allegedly meant to empower women, and many times even do, but still they punish those who fall out of what they deem appropriate femininity through ostracization or exclusion.

These campaigns that fight for traditional femininity are frequently focused on a White upper-class interpretation of femininity, ignoring that oppressed women experience femininity with far more complications. Even when women of color “succeed” at femininity, they don’t reap its benefits – Black women are masculinized and denied the privileges of being “feminine”, while the reward of femininity for Asian and Latina women often comes wrapped in hypersexualisation and fetishism.

The popular understanding of girlhood is inaccessible – to women of color, queer women, poor women, but even to women who do possess systemic privilege but just don’t conform to those ideals. It dangles the shiny idea of unbreakable bonds between women over our heads, but many of us will fail to meet the qualifications of any of it falling in our laps. Almost all women will eventually fall short of the ideal. So feeling an alienation from contemporary “femininity” isn’t a sign that something is wrong with a woman, but that something is wrong with the very idea of womanhood as femininity itself.

Despite all my criticism, I don’t think any of what I’ve discussed comes from some deep, evil desire among young women to gatekeep womanhood from each other. To the contrary, it seems the growing awareness of the frequently bleak material conditions of women has created a desire among younger women to grasp onto something — anything at all — that can unite every single one of us as inherently woman-like beyond our shared status as second-class citizens. But it won’t ever be useful to turn womanhood into an aesthetic or define a “Girl’s Girl” as a series of personality traits and interests you can check off. Any such attempts will always push some of us into the margins, ultimately hurting us all in the quest for women’s liberation.

To truly internalize what many of us preach, that gender and the norms and mores that come with it are a “social construct” with little basis in reality, means we have to come to terms with one thing: girlhood is a mythology of our own making. It is rife with contradictions and hypocrisy and never a one-size-fits-all. This is not a particularly easy thing for young women searching for solidarity and community with each other to come to terms with, and understandably so. But our eventual liberation from the confines of this deeply flawed social category that keeps us in constant competition with each other depends on it.