The Problem With “Women in STEM”

Image Description: Digital art of a small woman with black hair and lab coat sitting inside a test tube. At the top of the test tube, two yellow snakes wrap around the outside of the glass with their tongues out.

Design by Kate Vedder

The modern-day Wonder Woman no longer wears spandex and gold bangles. She trades her old uniform for a white lab coat decorated with a stethoscope and a much needed cup of coffee after a ruthless night of work. Notoriously known as a “woman in STEM”, she juggles hours of clinical volunteering, rigorous pre-med classes, and extracurriculars designed to aid her grad school application. Raised on programs that empower young girls’ scientific aspirations, she has the confidence to conquer the scary world of male-dominated fields. She takes pride in entering a profession from which many women were previously barred.

With enough perseverance, sacrifice, studying, and grinding, she too can achieve what men are expected to do.

This growing girlboss mindset has changed the demographic of Western academic institutions. In America, around 50% of biological scientists, medical residents, and undergraduates in STEM fields are women. These equalized rates easily lead observers to believe oppression in scientific institutions no longer exists. Girlboss rhetoric and empowerment have solved the systemic problems in academia!!! Or so many think.

The initial purpose of women in STEM movements was to create space for women in predominantly male scholarly communities. At the time, this was a novel and necessary goal, but when treated as the sole aim rather than a first step, the initiatives fail. These efforts have perpetuated harmful social expectations for women and have created exclusive boundaries within scientific fields which still need to be addressed.

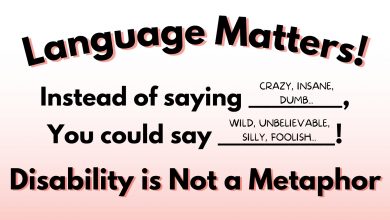

Women in STEM initiatives perpetuate systemic discrimination of academic institutions by failing to support all underrepresented individuals. The inherent gendered terminology puts a spotlight on those who identify within the gender binary, leaving non-binary individuals in the dark. A study conducted in 2023 found that non-binary individuals are 10% more likely to drop out of STEM than cis-individuals. This disparity is a result of the unwelcoming communities of these fields, but a lack of attention and data surrounding this gap leaves much to be discovered. Other issues of exclusivity in these movements arise in the lack of support for BIPOC women. Educational development programs focused on nurturing scientific passion require extra funds unavailable to underfunded schools, which are usually made up of diverse student bodies. This leaves BIPOC children with practically no support, and sometimes even lacking basic introduction to science, decreasing the likelihood of scientific pursuit at a higher level. While this article does not dive into the roots and effects of these inequalities, conversations around these subjects are critical to implement changes and promote inclusivity. It is vital to include these marginalized groups in the next steps taken by women in STEM movements as they work to address current problems that affect even those who benefit most from these initiatives.

One of our first lessons as Westernized humans is the dichotomy between perceived masculinity and femininity. Femininity is associated with meekness and a willingness to tend to others. Mothers are glorified as our primary nurtures; girls are given dolls to look after as a form of play, and early movie princesses are doe-eyed with an eagerness to follow their princes wherever they go. In contrast, masculinity is portrayed as a tough, motivated ideal removed of emotion. Extreme versions of this mindsents revolve around the idea that the masculine wastes time caretaking, when it can entrust cluttered emotional baggage to the emotional expertise of femininity. The average person will not believe this rhetoric to be the touchstone of truth, but watered-down versions of this sentiment seep into our subconscious, warping our expectations of the feminine.

Heteronormative associations of women with femininity manifests in constraining positions for women. Housewife, secretary, typist and other traditional feminine professions center around helping others embark on “admirable” work. Women are consistently portrayed as supportive accessories. Feminist movements beginning in the late 19th century slowly challenged and counteracted these ideals, making space for women to be more ambitious in their career paths. However, social constraints due to expectations of femininity continue into these new positions.

An ambitious girl is encouraged to dream of devoting herself to the grindset of STEM culture, but only in positions where she can still fulfill her womanly duties of caring for others. The professions with high female retention rates are those in medicine, psychology, and life sciences. With female therapists dominating the mental health industry, women are still the primary emotional support systems for others. As doctors– primarily specializing in gynecologists and pediatrics– women work tirelessly tending to their patients’ wounds and listening to their needs. Sound familiar? In contrast, a severe gender employment gap prevails in hard sciences and specialities such as engineering and mathematics. The disheartening inequality and lack of women in leadership within academic institutions raises suspicion about why women succeed in contained caretaking roles. This is not to say that these careers cannot be fulfilling for those who truly find passion in them, but for those who are pursuing them because they were taught to believe these pathways will earn them respectability, is it worth it?

Without leadership-oriented training and role models in leadership positions, women entering STEM often get stuck at entry-level positions with dwindling pay. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found that in 2019, a mere 26% of leaders in STEM were women, highlighting academia’s persistent and rampant inequality. This imbalance of power has been linked back to imposter syndrome, lack of mentors, and misogynistic biases (on all sides). Women report either feeling inadequate for positions they are overqualified for, or do not want to put in the effort applying when they know preference will be given to their male peers. This leaves women to conglomerate in a lower level of their field. This increased female population results in a decreased pay to their positions. Dwindling salaries are evidence of the lack of respect women are treated with in their careers and products of unaddressed misogyny in the workplace. As these unjustified wage cuts happen, many women do not know how to properly negotiate against the prejudice, and may even think it was inevitable due to imposter syndrome. Organizations that foster scientific passions in women and encourage them to go into these cut-throat positions leave them to be prey, providing little support in how to debate wages and promotions. Implementing support systems to develop these skills in female scientists could help combat these issues, but currently the problem remains unaddressed.

Programs aimed at fostering scientific passion in young girls instill an idea that modern-day success is accomplished by involvement in medicine or research. With television, social media, and teachers pushing images of scientists as heroes, impressionable minds internalize the concept that to be ambitious is to go into STEM. K-12 programs focus on building female academic confidence, reinforcing the belief that these fields are worthy of attention and dedication. While providing opportunities for individuals with a passion for science to cultivate their skills, programs surrounding the humanities remain underfunded. there remains a lack of funding for humanity based programs. The emphasis on the importance of science unconsciously tells kids whose passions lie in arts, entrepreneurship, and more, their dreams are not as important.Without immersion to other careers, many force themselves to develop a falsified and performative passion for STEM that drains their academic and creative energy.

When an individual does dare to venture into humanities or social sciences, they are often met with light-hearted ridicule charged with disappointment. Persistent messages regarding the necessity of the next generation to close the academia gap creates a pressure on young students to take up arms in the fight. If someone opts out in pursuit of another passion, their peers may look upon them with a higher-than-thou resentment. This is often seen in the pitiful remark of someone being “weeded out,” aka, not being strong enough to handle the rigor of STEM. These beliefs create a hierarchy of perceived intelligence, with back-breaking dedication to science at the top. By discrediting the powerful work done by others, women in STEM and women with non-traditional careers are detrimentally pitted against each other. The need to defend their respective capability is a waste of energy that could be used to unify against the patriarchal system that oppresses them.

Lack of encouragement, and even shaming, of careers surrounding artistic expression leads to disparities in a vast array of critical careers. From stand-up comedy to architecture, women are underrepresented and face similar issues of wage gaps and imposter syndrome. The lack of enamoration with these positions gives their issues less attention and support. Without organizations aimed at advocating for these rights, women in these fields are left to navigate patriarchal struggles alone. Those in these unsupported fields also face constant undermining, with female-dominant fields such as English and gender studies being seen as “easy” and sometimes “unimportant”. These majors are often subjected to being the brunt of jokes and degrading stereotypes, such as the English major barista. The social scoffing at female dominated professions where caregiving is traded for creating is evidence of the careers society expects and allows women to pursue.

The label “women in STEM” can be a powerful and unifying term, but without careful consideration of its connotations, the phrase can counteract the progress it is trying to make. It’s critical to re-evaluate the expectations we are socialized to project onto women and make active steps in supporting all minorities into their respective passions.