Your White Boy of the Month Is Perpetuating Racism

Image Description: An image of Timothée Chalamet with a yellow/orange sun behind him. In the background is a white and red calendar. Over the calendar are the words “WHITE BOY OF THE MONTH” in bold red print.

Design by Sydney Gaw

Have you seen the up-and-coming pale, gorgeously ugly, curly haired stud? You know the one! He’s absolutely to die for, especially in that one edit! Oh, come on, you know him! No, not Timothee Chalamet … where have you been?! Not Jacob Elordi or Jeremy Allen White … Well, if you haven’t seen the recent white boy of the month yet, don’t worry; he’ll find his way into your media consumption, whether you’re seeking it out or not. Yes … he does look awfully similar to his numerous predecessors, but he’s so baby!!!

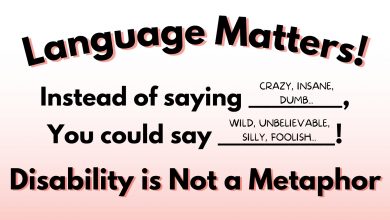

In case you were worried about Hollywood’s white boys losing their social power… don’t be. The “white boy of the month” trend provides consistent assurance that white men still have the ability to maintain an unrelenting hold over an audience’s lust and attention. With each media trend cycle, a “special” white boy is thrust into the center of online communities. During their time in the spotlight they may be subjected to a series of indoctrinating processes such as: having thirst trap edits made of them, ranking against their predecessors, objectifying comments left under their social media posts, and “babygirlification.” The trend is painted to be satirical — a jest at the absurdity of stan Twitter’s obsession with sexualizing celebrities. But if a joke is told enough times it loses its irony, and in this instance, perpetuates racism. Despite these effects, the trend avoids criticism and scrutiny through the “comedic” lens it is portrayed through.

This is certainly not the white boy’s first time being the object of teenage obsession. Propelled by their Anglo-Saxon features, famous white boys have been the pinnacle of admiration since the beginning of Hollywood. American films spotlighted actors such as John Wayne and Clint Eastwood for their rugged masculinity and athletic build. Their heteronormative attractiveness and public personas helped them cultivate a predominately female fanbase who romanticized them as ideal partners. These fanbases were critical for growing industries, as members drove content engagement when it featured their beloved stud. With the emergence of interviews and publicity, preceding generations of male celebrities curated even more intimate relationships with their fans. In the early days of social media, individuals were able to connect over their love of early 2000s stars, solidifying the power of “fangirl” culture and its influence on the media industry.

Celebrities supported by these passionate fan bases used to embody traditional masculinity, but members of the “white boy of the month” club tend to stray away from these norms. Overt muscle and facial hair no longer adorn lusted-after celebrities, and instead the “soft boy”— those with a sickly pale complexion and skinny physique— find popularity. These men have been classified as “ugly hot;” their attractiveness is defined by their deviation from certain aspects of beauty standards.

This shift away from stereotypical masculine appeal has baffled many who cannot fathom why “pretty” girls go for “ugly” guys. Some have tried to explain it with the Pete Davidson Effect, where “ugly” men become more attractive due to the influence of public opinion. The hypothesis claims the validation of one “pretty” girl leads to an increase in her partner’s value. This line of reasoning degrades men, reducing their worth to looks and minimizing them into relationship accessories. It also condemns women for their dating choices, reinforcing a deep rooted idea that women are incapable of making their own decisions.

In reality, this rise of the “soft boy” parallels the emergence of a critical feminist movement and cultural shifts. The 2017 #MeToo movement united victims of sexual harassment, bringing social awareness to the widespread mistreatment of predominately women at the hands of men. In response, women began to feel safer with femininity, viewing places and people void of the villainized masculinity as safer. This led to decreased preference for traditional masculine beauty standards, as soft feminine features offered a sense of security. In an interview with Refinery29, psychologist Dr. Claire Hart explained how individuals associate personality traits with certain looks. People have moved away from evolutionary reproductive cues such as muscle mass, and now gravitate towards those who “look like” they will treat their partner with respect and kindness — traits that toxic masculinity stereotypically lacks. People believe that personalities are now visually identifiable, with non-traditional looks indicating a dateable character. This harmful belief perpetuates the sexist notion that masculinity is incapable of emotive gentleness, and negatively impacts people who still fit into traditional beauty standards.

The candidates for the “ugly hot” and “softboy” craze all have one thing in common: their whiteness. Looking at BIPOC male celebrities, there seems to be a disproportionate number who fall into near impossible levels of traditional masculine beauty. Writer and actor Hassan Minhaj commented on this reality in an interview with VanityFair: “You know how there’s a whole class of white dudes of just like schlubby dudes who went to high school with me but now made it in show biz? … You gotta have like the V-taper in your abs … You gotta be Daniel Dae Kim-ripped.” These expectations stem from racist stereotypes, such as Black men being more athletic than white men, and force BIPOC men to emulate traditional masculine whiteness if they want to be seen. This is visualized in a curated 2018 “white boy of the month” calendar, where Michael B. Jordan — a standard for attractive masculinity — is the only BIPOC man listed. In the calendar he is assigned to February for Black History Month. The inclusion of MBJ is a performative step towards inclusivity in a growing age of ineffective digital wokeness and activism. Including a BIPOC man in a space created for praising white men creates a sense of harmful “colorblindness.” His inclusion does not change the overall message that white men are the epitome of physical attractiveness, which negatively impacts BIPOC men’s internal and external perception of their own worth.

These double-standards put BIPOC men in an inescapable loop of harmful expectations. If they do not fit into masculine Anglo-Saxon standards, they are made to feel ugly and invisible. At the same time, if they fit this rigorous criteria of washboard abs, symmetrical faces, and white features, they are grossly fetishized. There is no middle ground for BIPOC men. There is no room to be average, whereas white men receive praise simply because they are white bodies. Society maintains the ongoing negative stereotypes of masculinity by only giving BIPOC men visibility when they fit a masculine ideal. This phenomenon is exemplified in how white boys are adorned with social worship for moving away from traditional constraints, while their BIPOC counterparts face ridicule and scorn for the same actions. Part of the infamous “white boy of the month” Harry Styles’ persona is his willingness to defy gender norms in fashion, as he commonly integrates feminine silhouettes and bright colors into his look. His fans praise him for his bravery in challenging how men present themselves on and off stage, but Styles is not the first to make these steps forward. Several BIPOC artists such as Prince and a multitude of BIPOC drag queens have been pushing the masculine boundaries of fashion for years. While their actions are not completely forgotten, they are overshadowed by the praise of Styles’ perceived pioneering of these fashions. Black gay artist Lil Nas X also embraces gender exploration in his clothing, but does not receive the same exhalation Harry Styles does. Further, Lil Nas X’s queerness and blackness makes him susceptible to being attacked with villainizing labels. Coincidentally, white and unlabeled Harry Styles rarely receives such comments, and if he does, is quickly defended by his fanbase. The social support behind white men’s feminine exploration of their image allows them space to successfully separate from the “look” of toxic masculinity. The ridicule or erasure of BIPOC men’s same efforts leaves their masculinity to be emphasized in the public eye, promoting harmful stereotypes that they are aggressive and dangerous.

BIPOC men are rarely represented in the media, and when they are, they are almost always in the shadow of their white counterparts. While this has always been an enormous and discouraging obstacle for BIPOC men in the entertainment industry, the “white boy of the month” trend only makes their challenges harder. As the trend progresses, a white boy of the month emerges whenever one of his projects is thrust into the social spotlight. His devoted and widespread fanbase offers producers a large audience to market content involving the adorned boy to, as they know they have a reliable, built-in network of consumers. This leads to more interviews, media coverage, and professional offers for the glorified celebrity. His social media popularity expedites his career into Hollywood, making him the focal point of attention following a project, leaving the men of color and all of the women who participated in the same project behind. With dwindling representation in entertainment, the sole spotlight on white artists is detrimental to efforts to increase the field’s diversity and limit opportunities for BIPOC individuals. Since white actors and their devoted fan bases are guaranteed to bring in large box office numbers, they are more likely to be offered protagonist roles. This leaves BIPOC men with filler roles that often perpetrate racist stereotypes. Common demeaning archetypes — such as the black best friend or the gangster — continue the portrayal of BIPOC men as accessories or threats to white communities. These roles are not overtly offensive, and therefore avoid widespread criticism, but their constant repetition with little deviation makes them derogatory. This acceptance of BIPOC men as background characters causes the archetypes to re-emerge time and time again, causing audiences to internalize the racial stereotypes they perpetrate. Without a consistent exposure to BIPOC men in leading roles with emotional and humanized development, audiences fail to see them in these roles in day-to-day life.

“But that’s just media,” right? Yes it sucks, but it’s not like you’re actually racist for supporting semi-cute white actors … right? While our tendency to praise white boys is not directly targeted at BIPOC men, it is a reflection of our racial biases. In her book “The Dating Divide,” Celeste Curington examines how these biases play out on dating apps and the emergence of digital-sexual racism. Studies have shown that BIPOC men have less success on dating apps compared to their white counterparts. These everyday men are no Denzel Washington, but there is no space allocated to allow for them to be deemed“ugly-hot.” This in between does not exist for BIPOC men; they are either deemed overwhelmingly attractive or ugly. The increased standards put upon them and the lack of acceptance of their “averageness,” they are not deemed worthy of pursuing by both white and BIPOC women. While we may try to blame this on having a “type,” Curington dismantles this cover-up: “Preferences have different meanings depending on where you are located in a racial and gender hierarchy, a desirability hierarchy, as well as within online dating.” When we are faced with the effects of our white-washed “preferences,” we must consider how much of that “preference” is socialized racism.

The “white boy of the month” is supposed to be a joke — nothing more than a trend to mock white men for doing the bare minimum. However, many do not realize how the trend perpetuates systemic racism and negatively impacts BIPOC men. Teenagers will inevitably gravitate towards celebrity crushes, but imposing restrictive terminology limits who is worthy of being “attractive.” If we continue to encourage this narrow perspective, our racial biases will never be challenged, leaving us in a white-washed cycle of idolized men.