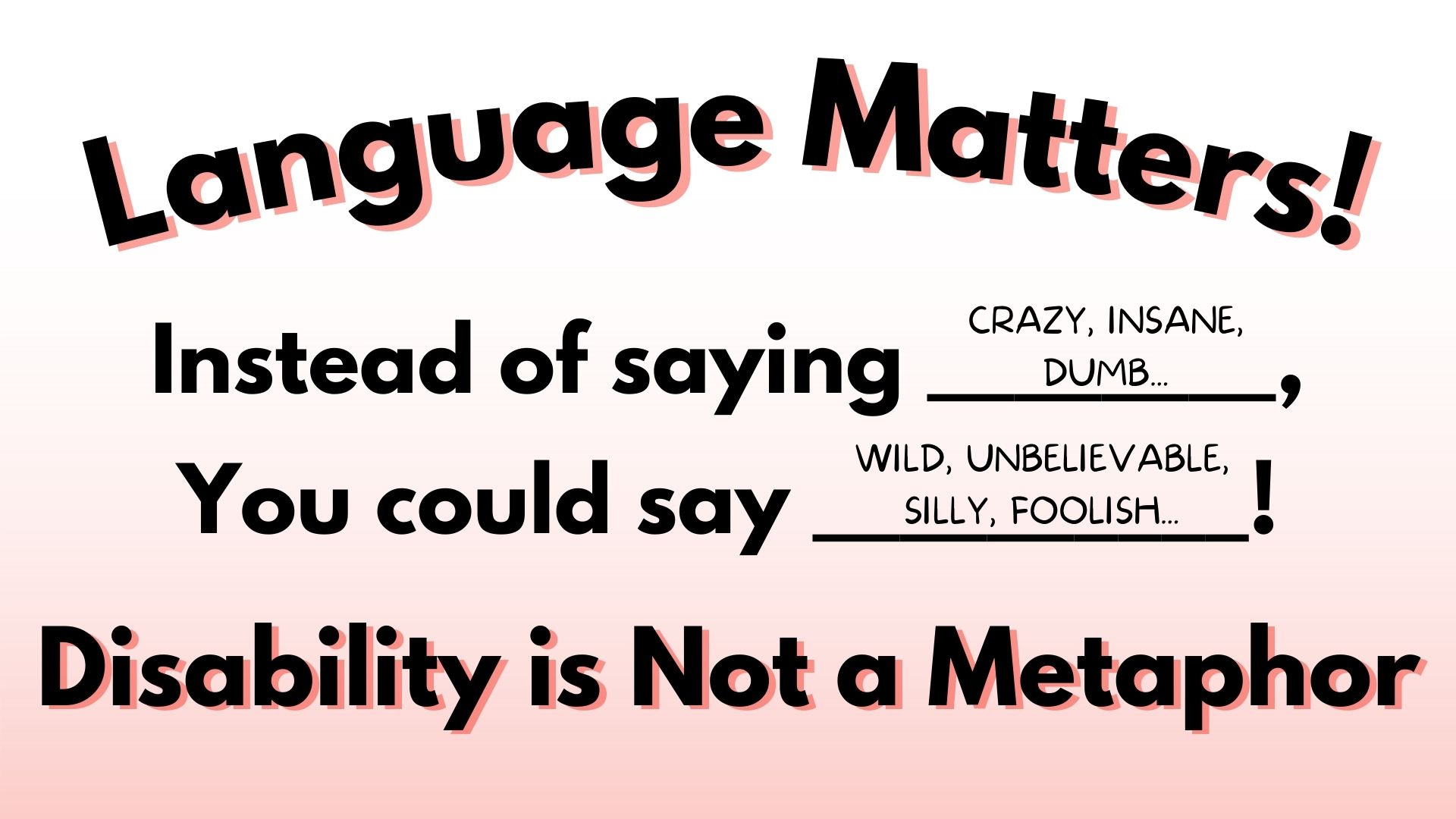

Disability is Not a Metaphor

Image description: Black text on white and red background reads: “Language Matters! Instead of saying crazy, insane, dumb…, you could say wild, unbelievable, silly, foolish…! Disability is Not a Metaphor”

Disabled people and their experiences are not metaphors.

Still, we often co-opt disability terminology and utilize casually ableist language for other purposes.

Nearly all of the language we have to talk about disability relies on assumptions that disability means loss, aberration and dysfunction. We accept without critical reflection that disabled people and experiences are lesser than and believe that language about ability can and should be co-opted to describe people and experiences that align with ableist understandings of intelligence and wholeness. Many of these words and phrases are so deeply normalized that we do not even recognize that they either were or still are used to describe and denigrate disabled people.

At worst, we use disability terminology to stand in for something terrible, frightening or dysfunctional, and at best, we use it to describe something abnormal — reinforcing the extremely common assumption that ‘normal’ means able-bodied.

A typical example: you see someone with a bad take on social media, and you respond by calling them “dumb” or “idiotic.” While you’re probably not thinking about the ableist roots of these terms, your language is still harmful. Even beyond the r-word or clearly abusive language, our vocabulary relies on words that historically have been used to classify and demean disabled people.

Look up the definition of the word dumb, and you’ll see that it is used to mean “lacking in intelligence” as well as “lacking the power of human speech.” Idiot can mean “a foolish person,” but it was also used as early as the 14th century to refer to someone who was not able to read or who was perceived by others as mentally deficient.

Other insulting terms you might hear regularly include moron, imbecile, stupid, and lame. All of these have been used colloquially or within medical and psychological discourse to violently identify disabled bodies as deviant and deficient. “Lame,” until very recently, was widely recognized as a specific descriptor for people who had difficulties using their feet and legs to walk. Today we use these terms to mean “bad” or “unintelligent” without thinking about where our linguistic resources come from.

Ableism in our language goes deeper than insults. When you use a disability, such as blindness or Deafness, as a metaphor for your experiences as a person who is not blind or Deaf, you minimize the experiences of disabled people and demonstrate an ignorance towards what those terms actually mean. We must recognize how those terms have historically othered disabled people and deprived them of autonomy over their own bodies.

As a seeing person, you are not “turning a blind eye” to anything. As an able-bodied person, you are not “crippled with worry,” and your love for a certain musician or actor is not a “crippling obsession.” Your hearing professor, while he may be ignorant, is not “tone deaf.”

Watering down disability language to suit able-bodied people’s desires ignores the existence of real disabled people and their very real needs.

Disability as metaphor also applies to mental illness and harmful psychological terminology. You might have heard that you should not refer to yourself as “bipolar,” “schizophrenic” or “OCD” if you do not actually understand and identify within those categories, so why do you feel okay calling yourself “dumb” for not knowing how to answer a test question or jokingly saying “I’m so blind” after briefly not seeing something that was right in front of you?

Once you notice how much of our language is casually ableist or relies on disability as a metaphor, you will begin to see it everywhere.

Words like “crazy,” which have come to encompass an almost endless range of feelings and emotional states (from extremely disconnected from reality, to enraptured or simply forgetful), still have not lost their pejorative psychological connotations. Who is labeled as “crazy” is undoubtedly racialized and gendered, since white heteropatriarchal norms underlie our basic ideas about what is real and what isn’t — and therefore what it means to be (in)sane.

This isn’t just symbolic. Ideas about craziness and insanity justify everyday and state-sponsored violence against the unhoused, against people of color, against queer and trans people and certainly against disabled people. Women with mental illnesses who report sexual violence are much more likely to be legally dismissed and branded as “crazy” liars, despite disabled people in general being much more likely to experience sexual abuse, assault and rape.

In countless ways, disabled people are disempowered and subjected to violence through cultural norms, legal systems, and policing practices that deprive them of autonomy over their own bodies.

Casual and explicit forms of ableism do not just show up in our language or our laws, but in many other forms of representation as well. Popular literature and media are full of ableist narratives that play off of our assumptions about disabled people. Many classic horror movies and tropes rely on harmful misconceptions about mentally ill and disabled people, reinforcing stereotypes and eugenicist ideologies. This continues to influence the horror genre today, such as the depiction of Ruben in Ari Aster’s “Midsommar,” whose facial disfigurement is meant to be deeply terrifying and ominous.

Disabled bodies in these films often stand in as symbols for evil, and mental or physical disabilities are weaponized as convenient explanations for antisocial behavior and interpersonal violence. These kinds of representation contribute to broader perceptions of disabled people as violent, threatening to society, and in need of institutional control.

Disability terminology, like disabled representation, is warped by ableism. It is crucial that disabled people have control not only over their bodies, but over the language they use to describe themselves. This language does not follow a strict set of rules, as disabled people do not all have the same experiences or terminologies, but it is crucial for us all to reconsider the kinds of words and phrases we use to understand our own subjective encounters with (dis)ability.

It is important for disabled people to reclaim terminology that has been weaponized against them for liberatory purposes — for example, identifying around the historically pejorative term “crip” has been a powerful tool for many disabled individuals and communities. However, casually ableist language is nearly always used without attention to the contexts in which it originated. Able-bodied people continue to speak for disabled people and insist that we are not capable of naming and identifying ourselves, or that we should be comfortable with the terms they have decided to use for us.

Interpersonal and structural ableism has not been radically transformed and still relies on discriminatory language. Instead of holding on to language with ableist roots on the grounds that these words have been “reclaimed” or that they “mean something different now,” we must transform how we think about difference and disability by reconsidering the relationship between language and power.

Accessibility requires making our language inclusive and sensitive to historical meanings, intersecting identities, and the ways in which our experiences are not all the same. You might not have a negative association with casually ableist language — in fact, you might even intend to use a word like ‘insane’ to describe something positively. Ask yourself, though, what are you really trying to say when you call something insane? Are you actually reclaiming the term, or are you using it as a metaphor for something else?

Changing the language we use is not about pitying or infantilizing the disabled community and its wide variety of members. You might not always know how someone identifies or how they would like to be addressed, as this differs from person to person.

Disability is not a static category or fixed identity; anyone can enter it at any time, and no one person experiences disability in the exact same way. Therefore, it’s crucial that we reject ableism by embodying anti-ableism in our words and actions, supporting structural change for disabled people, and critically engaging with the works of disability justice activists and scholars.

We must not fail to recognize the immense interpersonal as well as the institutional and ideological power that language has.

Some ableist terminology and alternatives (note that all of these are context-dependent and this is in no way an exhaustive list):

| Instead of saying.. | You could say… |

| Crazy | Wild, Outrageous, Unbelievable |

| Insane | Absurd, Silly, Foolish, Incredible |

| Blind | Unaware, Ignorant, Not Knowledgeable, Oblivious |

| Lame | Bad, Annoying, Boring, Dull, Tedious, Tiresome, Bland, Humdrum, Corny, Sucky |

| Stupid, Idiotic, Dumb | Frustrating, Ignorant, Dense, Silly, Foolish, Unbelievable |

| Tone Deaf | Insensitive, Out of Context, Oblivious, Out of Tune, Careless, Thoughtless, Inconsiderate |

| Bipolar | Unstable, Erratic, All Over the Place, Back-and-Forth |

| Psycho | Strange, Dangerous, Violent, Murderous, Threatening |

| Paralyzed | Frozen, Shocked, Numbed, Immobilized, Petrified |

Avoid describing your everyday experiences using language about strokes (like jokingly saying that someone must have had a stroke because they aren’t making sense), paralysis, seizures, PTSD, or other serious disabling conditions. Disability is not a punchline.

Unlearning ableism means changing your vocabulary. If you are not willing to do that work, you are participating in reinforcing an ableist status quo. However, changing language is only one part of making the world safer for disabled people. We must care for one another, reject harmful representations of disability, and hold all of our institutions accountable for enforcing and perpetuating ableism.