A Tomboy Story

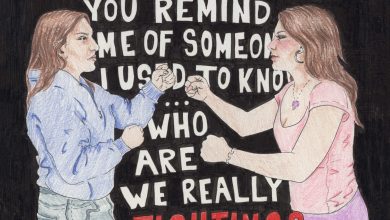

As a feminist and ex-tomboy, I often think about how my expression of gender has evolved over the course of my life. I’m still unsure whether my childhood identity as a tomboy, and my later decision to spurn this identity, arose from a desire to conform or from a genuine shift in my sense of self. My attempt to make sense of this change involves a lot of self-reflection and some crucial realizations about the limitations of the tomboy label.

According to Oxford Dictionary, a tomboy is “a girl who enjoys rough, noisy activities traditionally associated with boys.” While this definition is based on harmful and unnecessary gender stereotypes, the tomboy label often validates and provides community for those who deviate from the norm. However, problems arise when young people are taught to hate everything associated with femininity, leading to internalized misogyny and body image issues from a young age. It’s also no coincidence that the archetypal tomboy, especially in 20th century literature and pop culture, is white, straight and middle class.

Tomboy was, for me, an identity. It was a label for girls who were independent, curious, and maybe a bit too adventurous at times. Before embracing the tomboy identity, I had been a quiet and cynical loner. Afterwards, all of my friends were tomboys, and we bonded over our mutual disgust for princesses, fairies and all things pink. We played rough, spoke rudely and stayed out after dark. Basically, we were rule-breakers, reveling in the independence and solidarity of tomboy-hood.

A part of me misses the young me that had the courage to stray from the norm when it came to the behavior expected from young girls. However, my experience was also one that involved not wanting to be ‘like other girls,’ an issue that still plagues many adolescents and adults. I viewed anything ‘girly’ and pink as weak and felt guilty when I did enjoy these things.

My tomboy-ness was about destroying all aspects of my perceived femininity. This internalized misogyny from a young age led to strong feelings of self-hatred as well as hatred towards other girls my age. There were unspoken rules at play, constantly affecting my behavior and self-esteem. I remember going to the library and nervously checking out the cheesy YA romance novels, worried that this threatened my ‘tomboy brand.’ Tomboys were not supposed to like books. And they definitely weren’t supposed to like girl books!

But I was always secretly jealous of the girls who were clean and small, the ones who did gymnastics on the lawn every recess and lunch. They never got in trouble with authority figures. They were invited to all the birthday parties. They got all the attention. I loved my world, but kind of wanted to explore the ‘dark side’ (or rather the pink side), as I saw it.

Eventually, I did. I finally learned how to put my hair up, wear trendy clothing, and apply makeup (albeit badly) to my face. It wasn’t an overnight transformation, but I suddenly began to regret my tomboy days. How could I have cared so little about how I looked? No wonder people thought I was weird and gross. I was.

The tomboy in me died away as I began to see that popularity and attractiveness were now of utmost importance. The neglected bangs were chopped off, the basketball shorts replaced by booty shorts, and the girls I had once been so jealous of were now within arm’s reach. Putting on makeup and painting nails were just what teen girls did, I thought. I even learned to like some of these traditionally feminine activities.

My transition from tomboy to girly-girl was fueled by peer pressure and the bodily changes that I experienced as a teen. Social media, as well as new friends, made me see that by appearing more feminine, I could gain popularity, both online and in real life. One’s ability to appear feminine was deeply linked to social status.

So, I measured my self-worth with Instagram likes and by comparing myself to the prettiest and most popular girls I knew.

I also couldn’t ignore my body’s changes as I hit that wonderful age of puberty. The hormones were flowing, and so were my tears as I discovered the tiring and tedious procedures that were necessary to ‘maintain’ my body. Running through my brain was an endless to-do list. Tasks included: start wearing a bra (push-up preferred), apply deodorant daily, shave your underarms and legs, get ready for your period, and don’t forget to stay thin and appealing for the boys!

We teach young girls to hate themselves in subtle but pervasive ways. My fear of being weak and girly turned into a fear of not appearing feminine enough. We force labels like ‘tomboy’ onto young children, seldom allowing them to figure out their own personalities and identities. We tell children that everything they do and believe in is ‘just a phase,’ while at the same time sticking them with these labels that have tremendous life-long effects.

Many tomboys eventually come to identify as queer or trans, but many do not. Because of this, the tomboy experience is not simply one experience. Tomboys cannot all be characterized as confused girls, future lesbians, and/or wannabe boys. Why can’t adults let a child’s words and decisions speak for themselves? Why must we jump to labeling and psychoanalysis, as if we know exactly who a child is and will be just because of how they dress or who they play with?

Social and cultural norms are key in the construction of a rigid gender binary beginning early in life. Gender reveal parties, baby showers, and infant fashion are all displays of gender that associate and label preferences based solely on whether a child is designated male or female. Beyond the pink-blue stereotype, studies done in American preschools reveal that while little girls are often socialized to be polite, quiet and still, young boys are more often given the freedom to be loud, curious and even violent. The allocation of behavioral traits is not only a way of creating and maintaining order among children, it produces teens and adults who view the gender binary and behavioral sex differences as innate and natural. It allows us to start making claims about what’s normal and what’s not. It allows adults to start labeling ‘deviant’ children as tomboys, sissies, class clowns. These children are treated as inherently troubled youth, when gendered behavior and the binary are actually intensely and continually conditioned.

I don’t regret any so-called phase of my childhood. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with being a traditionally ‘girly’ child, and there’s also nothing wrong with ‘boyish’ or gender-nonconforming children. The enforcement of a strict divide between the two is what led to issues for me as a child who was compelled to constantly prove my girlhood (or lack of it). The idea that some girls are tomboys and some aren’t needs to be left in the past. On the whole, let’s teach kids to be respectful of gender diversity rather than reinforcing the binary with outdated and unnecessary labels.