Feminism 101: What is Pinkwashing?

Image by Emily Farag.

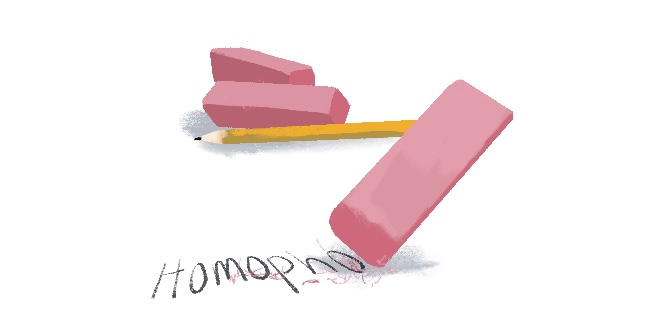

Pinkwashing is a term with multiple meanings, but most commonly refers to the deliberate appropriation of sexual liberation movements towards regressive political ends.

The first use of “pinkwashing” is credited to Breast Cancer Action, an organization dedicated to combating breast cancer at the intersections of social and environmental justice. A riff on the term “whitewashing,” defined as an attempt to conceal or dilute unpleasant facts, pinkwashing was coined in 2002 to critique companies that market products with a pink ribbon, which symbolizes support for breast cancer charities, while manufacturing or selling carcinogenic products.

Pinkwashing now commonly refers to the appropriation of the LGBTQIA+ movement to promote a particular corporate or political agenda. In other words, entities market themselves as “gay-friendly” to gain favor with progressives, while masking aspects that are violent and undemocratic.

Perhaps the most noted example of pinkwashing is Israel’s public relations campaign to promote itself as the “gay mecca” of the Middle East. This campaign emerged in direct response to “bad press” it received for human rights violations, particularly following global media coverage of the Sabra and Shatila Massacre.

Activists have problematized pinkwashing efforts as an attempt to mask and legitimize Israel’s human rights abuses against Palestinians, regardless of sexuality. Queer Palestinians are not spared when Palestinians are bombed en masse, nor are they given a free pass out of Gaza. They are not exempt from marginalization under Israeli apartheid, and in fact suffer compounded violences as hyper-transgressive individuals. Palestine’s queers suffer the violences of settler colonialism and occupation alongside homophobia and transphobia.

Furthermore, queer Palestinians are subject to epistemic violence as their identities are routinely erased and manipulated. Under a narrative that relegates queerness to non-Arab spaces, Israel binarizes their identities into the mutually exclusive categories of “Palestinian” and “queer,” while obscuring violence against Palestinians as a whole. Alternatively, Israel posits itself as the savior of Palestinian and Arab queers. Under this inherently orientalist and Islamophobic rhetoric, Palestinian society is deemed backwards and Palestinian queers in need of saving (by Israelis).

Israel’s campaign is particularly ironic in light of its lacking LGBT rights record. For instance, due to Orthodox religious law, Israel bans gay couples from participating in marriage and adoption. Along this vein, pro-Israel lobby AIPAC boasts the State’s progressive stance on LGBT rights, but invited renowned homophobe, Vice President Mike Pence, to speak at their annual conference. The premise of queer liberation is not used in earnest, but rather as a strategy to distract from other oppressions.

Pinkwashing is not exclusive to Israel, however; the radical right in the U.S and Europe readily employ pinkwashing strategies. Some in this camp have adopted loosely pro-lesbian and pro-gay platforms in order to recruit conservative queers to their cause. During her 2017 presidential bid in France, far-right candidate Marine Le Pen distanced herself from her party’s traditional homophobic platform by appointing gay advisors, Florian Philippot and Sébastien Chenu. Meanwhile, alt-right spokesman, Milo Yiannopoulos, blamed Muslims for the shooting at Pulse, an Orlando LGBT Nightclub. He exploited the tragedy to promote a racist, anti-immigrant, and Islamophobic agenda under apparent concern for “LGBT rights.” Similarly, the English Defense League, an ultra-conservative group based in the U.K., obscures xenophobic and anti-Muslim rhetoric under the premise of “LGBT freedom.” The League even contains an LGBT division, dedicated to expelling Muslims from England to “eliminate homophobia” in the U.K.

In “Rethinking Homonationalism,” scholar Jasbir Puar provides a useful framework for deconstructing the ideological power behind pinkwashing tactics. Puar coins the term “homonationalism” to describe how LGBTQIA+ people or their rights may become assimilated into nationalist, right-wing, or neoliberal movements. According to Puar, pinkwashing is rendered coherent as an appeal to Euro-American homonationalism, under which sexual modernity becomes “a barometer by which the right to and capacity for national sovereignty is evaluated.” In other words, an nation’s stance on the single issue of LGBT rights may recuperate all other forms of violence in Euro-American minds.

Ironically, those who employ pinkwashing are fundamentally homophobic, as queer liberation cannot be achieved without racial, economic, and all other forms of justice. Under superficial displays of solidarity, entities conceal their own complicity in queer oppression, as they continue to bolster intrinsically heteronormative systems of violence.

Pinkwashing undermines efforts towards genuine justice, using divide-and-conquer tactics to individualize oppressions. As queers are pitted against Muslims, people of color, and/or immigrants, each of these groups is rendered exponentially more conquerable. Movements that seek to dismantle systems of oppression must do so unconditionally, rather than promoting the oppression of other groups to make gains.

Perhaps most violently, pinkwashing erases the existence of queers in the communities the practice marginalizes. In constructing an “us vs. them” narrative, pinkwashers depict themselves (and the people to whom they appeal) as the sole proprietors of queer embodiment. In other words, queerness is conceived as exclusive to “the West,” denying the possibility of queer identities among the marginalized. Through the negation of “othered” queer identity, such as “Arab queer,” pinkwashing multiply marginalizes those who occupy the intersections of queerness and other sites of oppression.

Whatever the particularity of its meaning, pinkwashing refers to the exploitation of marginalized sexual identities to promote insidious agendas. In recognizing and countering its premises, individuals may reclaim appropriated movements, reorienting them towards meaningful, collective social change.