Fighting Fatphobia: A Feminist Take on Weight

Design by Nicole Nobre

Body positivity is trending. Examples in popular culture abound, from Instagram hashtags to ad campaigns, all of which send a clear message: no longer is it fashionable to hate your body.

As body positivity has gained cultural momentum, corporations have caught on. Whether it be prominent underwear brand Aerie incorporating plus-size models into their advertising (and reaping hundreds of millions in sales) or Weight Watchers rebranding as WW, companies everywhere have learned to co-opt the language of empowerment and inclusivity. The new cultural fixation is not on thinness but on healthy habits. Diets are replaced by detoxes or lifestyle changes; instead of weigh-in meetings, WW customers now attend “Wellness Workshops.” But underneath the veneer of self-love and acceptance lies the same insidious rhetoric that has fueled fatphobia in America for decades.

Fatphobia, or the oppression of fat bodies, has existed in various forms for centuries. Fat individuals face fat-shaming and weight stigma in a society that promotes thinness as ideal. Fatphobia also encompasses institutionalized oppression in employment, housing and healthcare. Though current body positive narratives purport to prioritize health over thinness, health and wellness are still equated with weight loss. Fatness is treated as a problem to be solved rather than what it actually is: an example of natural genetic diversity.

Unfortunately, fatphobia is often overlooked in analyses of intersecting axes of oppression. Many people acknowledge that fat-shaming is unkind, but do not consider fatphobia to be a significant form of oppression analogous to racism or sexism. Others believe that fatphobia is simply a concern about health, or argue that those who encounter fatphobia can avoid it by exercising personal control over their weight.

Such an analysis ignores the ways in which body size and fatness are profoundly political. Fatphobia disproportionately targets marginalized communities and intersects heavily with racism, classism and misogyny. This is both a cause and a result of the fact that in America, the fattest people tend to be from under-resourced communities of color. Fatness in the popular imaginary is heavily classed and racialized.

Sabrina Strings, sociology professor and author of “Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia,” traces the roots of Western fatphobia to the Atlantic slave trade. Race scientists in the 18th century suggested that Black people were “gluttonous,” linking fatness with notions of African “savagery.” Fatphobia, especially directed toward Black women, predated medical discourse that painted fatness as a public health concern. Fatphobia has never been about health, Strings argues. Rather, it represents “one way the body has been used to craft and legitimate race, sex and class hierarchies.”

The racialization of fat bodies deeply affects how they are discussed. In her article “The Color of Fat: Racializing Obesity, Recuperating Whiteness, and Reproducing Injustice,” political science professor Rachel Sanders compares public discourse surrounding the recent opioid epidemic to that of the so-called obesity epidemic. The opioid epidemic is largely understood to be a public health crisis that goes beyond individual blame. In the 2020 Democratic Party presidential debates, candidates repeatedly implicated pharmaceutical corporations, overprescription and rising poverty rates as causes of the epidemic.

Meanwhile, discussions of “obesity” and governmental interventions frequently rely on narratives of individual choice: public education campaigns such as USDA’s MyPlate or Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! Initiative; mandatory nutrition labels and calorie counts in restaurants; and local soda taxes. All of these efforts betray an underlying assumption that fat people just need to make healthier choices to lose the weight.

Unlike opioid abuse, which is acknowledged to be the result of broad social and economic factors, “obesity” is still largely viewed as a personal failing. It is no coincidence that while the face of the opioid epidemic is white and rural, the “obesity epidemic” is predominantly represented by a Black woman.

Weight has thus become an indication of self-control and morality. The thin person is the embodiment of the ideal, neoliberal citizen-subject who controls their health by making “good” choices. As Charlotte Biltekoff explains in her book “Eating Right in America: The Cultural Politics of Food and Health,” over the years neoliberal discourse has redefined health as a responsibility rather than a right: “Citizens were increasingly expected to make responsible choices as consumers, to adopt preventative practices, and to exercise self-discipline.” Under this new framework, it is no longer the government’s job to support the health of its citizens. Rather, we have a duty to the government to stay healthy, in order to maximize productivity and minimize national healthcare expenditures.

Therefore, those categorized as “obese” are assumed to have failed, not only in maintaining their personal health but also in their obligation to the state to be a productive citizen. Consider this rhetoric in the context of race and class politics: earlier we noted that the image of “obesity” in America is a Black woman — to be more specific, a poor Black woman who is a recipient of public benefits. Fatphobia thus collides with racialized fears of “welfare queens” to produce the image of fat Black women as lazy, deficient in self-control, and a drain on public resources.

Indeed, welfare is another avenue through which fatphobia is weaponized against the poor. Weight and health are commonly used to justify restricting or cutting funding for food stamp programs. In 2008, Michael Pollan suggested in the New York Times that “junk foods” be excluded from food stamp coverage. In 2016, New York Senator Patty Ritchie proposed a bill to prohibit the usage of food stamps on foods like soda, candy and cake. Several other programs across the country have implemented similar systems to promote the consumption of “healthy” foods.

These efforts are largely driven by the misconception that fatness is a result of overeating. In reality, most studies suggest that fat people eat no more than thin people do. Data from the CDC’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which was based on a sample of 20,749 people, indicated that “neither the caloric intake nor the caloric intake adjusted for physical activity level and age was higher in the obese subjects.” A similar study in the British Medical Journal surveyed 3,454 subjects and found a small but “highly significant” negative correlation between weight and caloric intake.

The idea that overeating causes “obesity” obscures the fact that the hungry can and do become fat. Food insecurity is one of the reasons poor people are likely to be fatter — irregular access to food causes metabolic and hormonal changes that promote weight gain. This is a natural physiological response to deprivation; when the human body detects the threat of starvation, it fights to increase fat storage as a survival mechanism. Attributing fatness to the consumption of “junk foods” — which tend to be the most affordable and energy-dense foods — further stigmatizes poor and fat individuals and diverts attention from the urgent risks posed by food insecurity and hunger.

Among the Left, the prevailing argument against fat-shaming is that those living in poverty have less access to “healthy” foods and therefore should not be shamed for their “unhealthy” weight. At first glance, this argument seems sound. Low-income people of color are disproportionately affected by food deserts or areas with limited access to nutritious and affordable food. We should certainly seek to eliminate food deserts, but not as a “solution” to weight gain — rather, because access to food is a fundamental human right.

Ultimately, any line of reasoning that ascribes fatness to a lack of healthy food relies on several false assumptions: the assumption that weight depends on individual choices and is therefore within the realm of personal control, that individual behaviors determine health, and that gaining weight is intrinsically unhealthy.

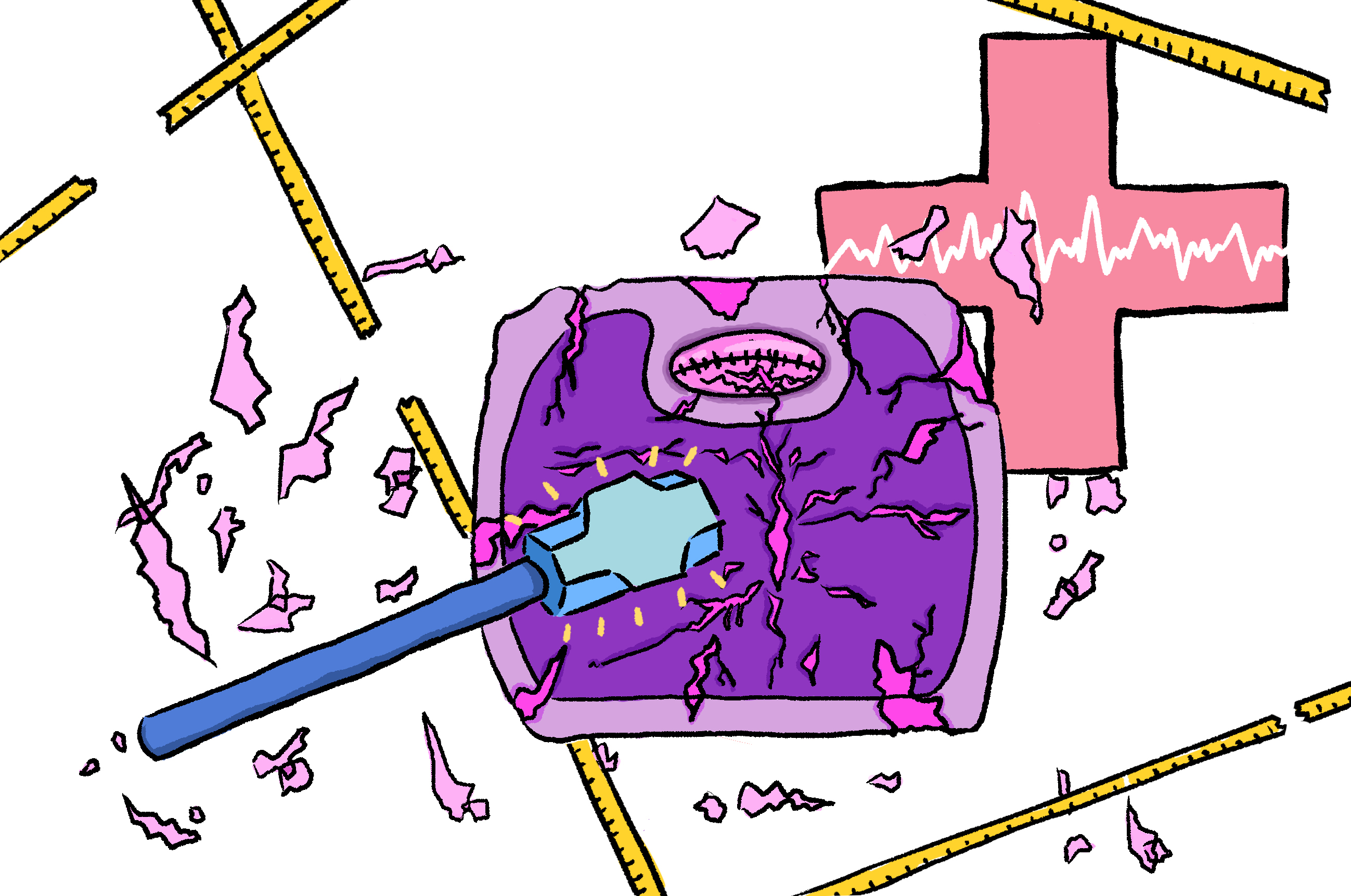

The widespread belief that weight is simply a matter of personal control is the reason the diet and weight loss industry in America is thriving. The United States weight loss industry is worth $72 billion, and 45 million Americans attempt a weight-loss diet each year. But for decades, the medical literature has shown that 95 to 98 percent of diets do not result in sustained weight loss. The majority of dieters actually gain back more weight than they had initially. This phenomenon holds true across all types of diets, whether the diet is based on calories, food type or macronutrients.

In fact, individual choices have limited effect on one’s health at all. According to the CDC, individual behaviors account for less than 25 percent of population health. Far more relevant are the social determinants of health: social class, poverty, access to quality housing and healthcare, discrimination, and stress, which can be affected by all the preceding factors and more. These socioeconomic factors impact the health of fat people far more than their actual weight does.

It is often taken for granted that fatness, medicalized as “obesity,” leads to poor health; this is because scientific studies have long shown correlations between fatness and negative health outcomes such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and shorter life expectancy. But most of these studies fail to take into account the confounding variables that predict both fatness and disease. In other words, correlation does not indicate causation — it is not fatness per se that harms health, but rather adverse social factors that disproportionately impact fat people.

For example, because fat people tend to belong to other marginalized populations, they experience oppressive conditions that lead to chronic stress. Stress is extremely harmful: it has been linked to insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, all of which are typically thought to be caused directly by fatness. Stress also predicts weight gain, because it increases the release of hormones that affect appetite and fat storage. Put simply: stress is unhealthy, and stress can cause weight gain, but weight gain in itself is not unhealthy.

Fat people are also more likely to diet and experience weight cycling, which is the repeated process of losing and gaining weight. A 2007 UCLA study linked weight cycling, or “yo-yo dieting,” to “increased risk for [heart attack], stroke, and diabetes,” which are all ordinarily attributed to fat itself. Weight cycling is also associated with cardiovascular disease, increased blood pressure and high cholesterol. In the end, weight loss attempts pose a greater health risk than fatness ever will.

In addition, fat individuals face weight discrimination, which further complicates their health. Weight discrimination has been linked to shorter life expectancy, mediated through factors like social isolation, stress and economic strain. It is near impossible to disentangle the health effects of weight discrimination from the effects of fatness itself.

Needless to say, weight and health are far from synonymous. Nearly all the supposed health risks of weight gain can be explained by the forms of oppression that are caused by and that intersect with being fat.

This is not to suggest that fat people must be healthy to deserve rights. Fatphobia would not be justified even if fatness did cause disease, because health is not a requisite for justice. But it is important to illuminate the relationship between weight and health because fat liberation requires being critical of narratives that stigmatize fatness. The understanding that weight is not indicative of health is key to uncovering the way fatphobia operates as a tool of social control; the medicalization of fatness simultaneously obscures the effects of oppressive power structures on health and blames fat people for their own oppression.

What we know today as body positivity was born out of the fat liberation movement of the late 1960s. Fat activists, inspired by contemporary social change movements, used confrontational, disruptive tactics to protest fatphobic discrimination. Fat Underground, a fat feminist collective based in Los Angeles, published the “Fat Liberation Manifesto” which explicitly identified the movement as “allied with the struggles of other oppressed groups against classism, racism, sexism, ageism, financial exploitation, imperialism and the like.”

Sara Fishman, co-founder of Fat Underground, explained the organization’s name: “its initials expressed our sentiments.”

If those of us who advocate for body positivity are to raise any real challenge to fatphobia, we must look back to the movement’s radical anticapitalist roots. Fatphobia is a deeply entrenched system of social, political, and economic domination, and no amount of woke lingerie brands is going to change that.