The Aesthetic of Health

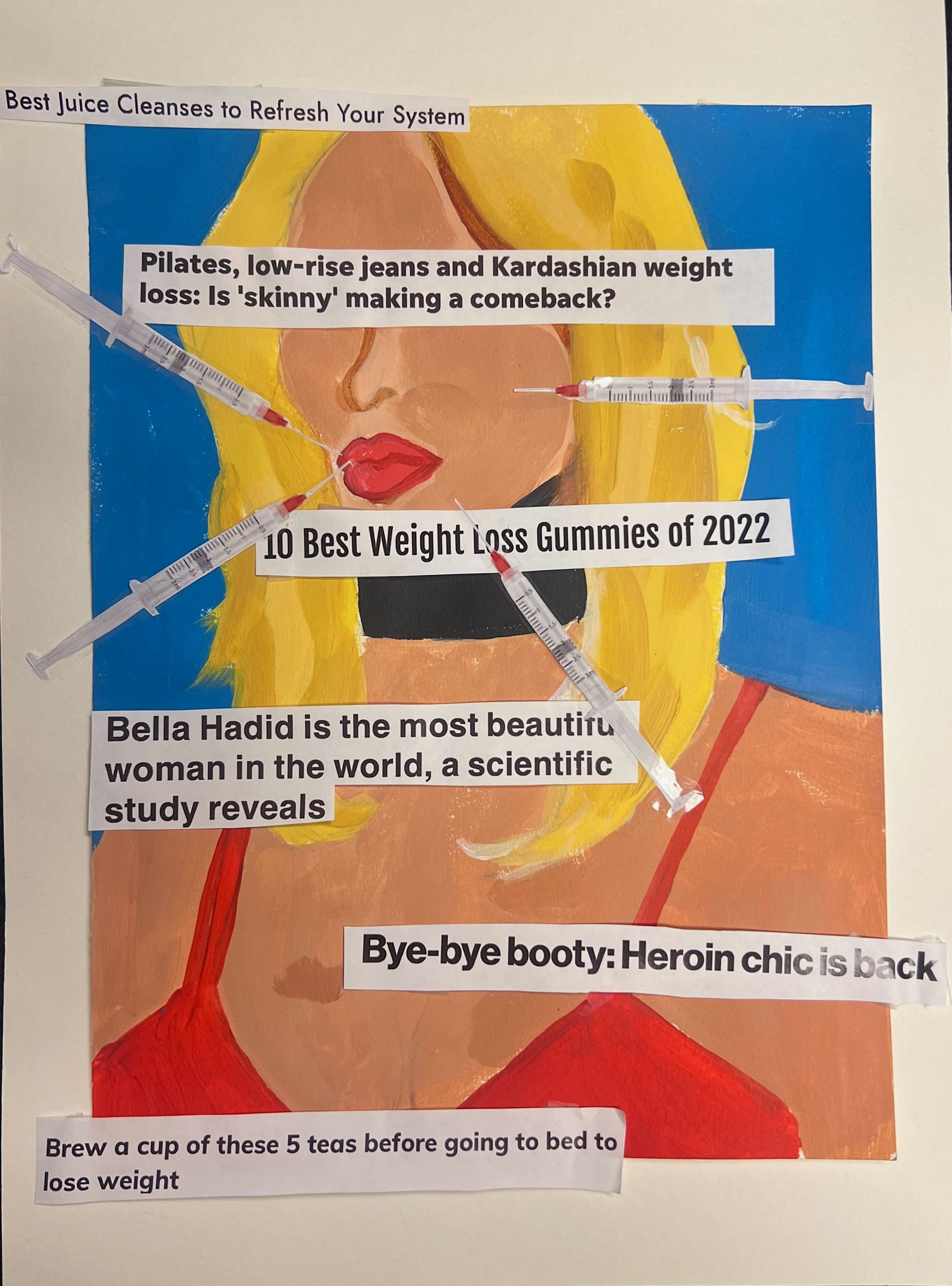

Design by Tia Barfield

Image description: A painting of a blonde white woman with four Botox injection needles comically inserted into her face and lips. Pasted over her face are various headlines: “Best Juice Cleanses to Refresh Your System,” “Pilates, low-rise jeans and Kardashian weight loss: Is ‘skinny’ making a comeback?”, “10 Best Weight Loss Gummies of 2022,” “Bella Hadid is the most beautiful woman in the world, a scientific study reveals,” “Bye-bye booty: Heroin chic is back,” and “Brew a cup of these 5 teas before going to bed to lose weight.”

Picture the average pilates-goer: she’s clad in Lululemon and deeply concerned about her gut microbiome, she eats enough vitamin supplements to cure a horse of scurvy, and, most importantly, she claims to be exactly what she is not — effortless. She’s white, cis, skinny, able-bodied, has flawless hair and skin that seems to be ever-youthful. She lives and dies by juice cleanses and keto diets, supplemented with sketchy, Instagram-ad gummies claiming to do everything from making hair grow to curing cancer. You might describe her as pretty, but you would definitely describe her as healthy.

Rather than physical fitness, however, what she embodies is an aesthetic of health, a carefully crafted form of beauty which she hides behind a smokescreen of indifference. She claims she doesn’t care about her looks and that she only wants to be “healthy” so therefore any criticism about her habits is unwarranted.

In recent years, social media influence has caused the line between health and beauty to blur. Some healthcare providers have become medically licensed beauty gurus, advertising and popularizing minimally invasive plastic surgery and injections with their followers. Instagram frequently features plastic surgeons, injectors, and dermatologists showcasing their services as well as advising users on medical procedures, leading to an increase in the interest in noninvasive cosmetic procedures. For those not willing to go under the knife or needle, skincare provides a noninvasive way to stay young and as a result the industry has seen massive profit growth spearheaded by an interest in anti-aging products.

Beyond skincare and plastic surgery, makeup is the next line of defense in the quest to look healthy. This decade’s trends have shifted to a new perspective of “natural beauty.” In theory, natural beauty means no makeup, lots of skincare, and showing off your “inner beauty” without feeling pressured to do a full face of makeup everyday. In practice, however, it means we expect femme-presenting people to look pretty 24/7.

This shift has, paradoxically, increased the amount of time and effort people put into their “natural” appearances. A study published in the Journal of the Academy of Market Science found that the increase in the use of the tag #NoMakeup actually correlated with an increase in cosmetic sales. In addition, the study found that the most popular #NoMakeup selfies were the ones rated most attractive, and the ones with the most makeup on.

Natural beauty isn’t just manufactured, it’s designed to be exclusive. A similar offshoot of the “No Makeup” look is the newly-dubbed “clean girl” aesthetic. While this style borrows elements like slicked-back hair and large hoop earrings from Black and Latina women, it also excludes them from fitting into the standard. The majority of people dominating the hashtag on TikTok and Instagram are white, while Black and brown women are called “trashy” for showing off similar styles. Just like the pilates-goer, the average “clean girl” is part of a highly exclusive group of young, white, rich cis women that claim to not care about their looks while simultaneously trying to show them off.

These exclusive beauty trends create an issue where in order to be seen as “healthy,” you need to fit into an ever-shrinking standard. Racist, fatphobic and ageist beauty standards aren’t new, but the new pressure to fit into them is. To be seen as beautiful is inherently exclusive, while to be healthy is something expected of everyone. When beauty trends focus on pretending not to be modifying your appearance, it increases the pressure to conform to them by masking the effort and privilege required to achieve them. Then, as we judge health by beauty, we assign a moral failing to those who don’t meet the standard.

This new pressure on an aesthetic of health over beauty also creates a strange paradox for many feminine-presenting people. They are told to both look pretty but shamed for putting in effort towards their appearance. A 2018 study found that when a subject was perceived as putting in more effort towards their appearance using things like makeup they were also perceived as being more likely to engage in behaviors the participants considered immoral. We call people who put in effort in vain and those who don’t slobs, creating a double standard that forces people to walk a narrow tightrope.

This shaming of “high-maintenance” behavior like doing makeup or hair everyday blossomed into the trend of natural beauty. However, even that still left room to be ridiculed (posting a #NoMakeup selfie and being called out for your lipstick has become a common yet embarrassing faux pas). Thus, the aesthetic of health was born: a way to fit into the beauty standard without being called out for it.

Under this guise of “health,” any claim of trying to look “pretty” (a morally reprehensible, deeply vain act) can be countered with the simple explanation that we’re trying to look healthy (something noble that everyone should strive for). However, this new bait-and-switch puts even more societal pressure on people to conform. It’s easy to see how conventional beauty standards arise from a deeply flawed racist, ableist, and fatphobic society, but a standard of health should be, in theory, achievable for all. This then shifts the conversation around beauty from being about a societal issue to a personal one, disallowing exceptions and actively shaming people who don’t fit into this standard as not trying hard enough.

One great example of a similar change is the transformation of movements against fatphobia into more generic “body positivity.” While originally many fat liberation movements were designed to fight against the societal discrimination fat people face, body positivity movements have shifted that focus towards celebrating each individual’s body. This shift takes away the blame of society for not accepting someone, and instead argues it is the individual’s responsibility to work towards self-acceptance. While self-acceptance is great, it doesn’t do much to combat the myriad of systemic issues fat people face, including stigmatization, lack of healthcare access, and increased rates of depression.

Societal ideas of “health” are already flawed before we add beauty into the equation. Fatphobia, medical racism, ableism, and misogyny all influence who we see as “healthy.” Appearance plays a huge factor in healthcare, patients are often told obesity is the cause of all their symptoms, and many doctors offer less effective treatments to patients of color. As the standard of health shifts more and more to Eurocentric beauty standards, this means increased healthcare disparities in a system that’s already drowning in them. As a result, this standard of health both increases the pressure people face to conform to the standard and also further distracts from the root causes of patriarchy and racism that create it.

To admit we want to be beautiful is a deeply shameful act. It is, firstly, to admit we are affected by patriarchal standards, regardless of what we may claim, and secondly to admit a deep, amorphous insecurity that we know will never be assuaged. What is much easier to digest is to say we want to be healthy. To claim that our efforts to improve our looks aren’t in vain but are actually part of a larger, commendable goal to better ourselves. This lie we tell creates tremendous issues, however, when suddenly beauty becomes more than just our appearance, but a judgment on our entire lifestyle.