The Inherent Sexism in Women’s Professional Clothing

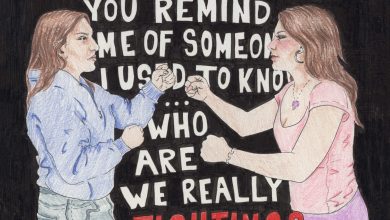

Illustration by Katherene Quiteno.

As summer crawls to a halt and winter fast approaches, “internship season” begins to round the corner. Standing in the chilly dressing rooms of Express and Ann Taylor stores, college-age women across the country are preparing for their first professional interviews. Though all applicants must polish their curriculum vitaes and resumes, women have an added layer of preparation and stress: what outfit to wear to the interview.

Many shrug off this obsession with finding the perfect pantsuit or jacket for an interview as foolish or self-absorbed, a superfluous gesture to the myriad other requirements of appearing professional. But it is a sad reality that perhaps a woman’s most significant choice that day will in fact be which pair of heels she slips on.

In interviews, a woman’s appearance heavily influences whether she is to be evaluated on the basis of her intellectual merit or solely on the basis of her gender. Many times, her choice of clothing may be the sole deciding factor in her success. In this way, standards of professionalism have become yet another extension of patriarchal power.

In a study for the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Dr. Sandra Forsythe studied the effects of clothing type during professional interviews for women. Predictably, the results of the study concluded that women donning “costume masculinity” — or clothing with more traditionally masculine traits — were more likely to be evaluated positively for management characteristics.

These conclusions tie back to a common perception in professional atmospheres: that men’s suits are intrinsically neutral, while women’s suits are specifically gendered. As a result, the femininity of an article of clothing is inextricably linked to how professional — or, more aptly, how unprofessional — it may be deemed.

On the flip side, appearing not feminine enough can also act as a detriment to a woman’s professional image. In a recent sociology study, researchers at the University of Chicago and University of California, Irvine studied the effect of personal grooming and conventional attractiveness on workplace interviews. Attractiveness was rated by the interviewer on a five-point scale from “very unattractive” to “very attractive.” For women, personal grooming included the application of makeup products. While attractiveness increased average salary benefits for both genders, personal grooming had a much higher effect on women.

In her article for the Washington Post, Ana Swanson reflects on these conclusions, writing, “The results suggest that beauty, especially for women, is more of a behavior — ‘something you do,’ rather than ‘something you are.’”

The combined effect of these two paradoxical studies leaves women in somewhat of a familiar bind: a woman must dress like a man to be taken seriously, but if she crosses an arbitrary line, she may similarly be considered less hireable or promotable. This ambiguity only increases when considering the individual preferences and standards of the specific hirer.

The results shed some light on the tangible ways in which structural sexism permeates workplace culture and operations. For many, however, the studies may come as no surprise. Sexism in the workplace is still a widely universal phenomenon, and the effects can be agonizing. Though women are more likely to succeed in school and to receive advanced degrees, we still must go to ridiculous lengths to simply prove ourselves capable — to show to an antiquated world that we still can, and we will, succeed.