The Isolating Conditions of Work

Photo by Austin DeArmond via Flickr

I didn’t realize that my home life and my school life would be so profoundly independent of each other in college. Sometimes when I’m at home, I miss the structure of a busy schedule — always having a reason to leave my bedroom. But the drawback of getting an education is the way school dictates my life. When I’m not in class, I still live on campus and have homework, and it’s so easy to feel trapped in an academic bubble where I’m out of touch with both the world outside UCLA and myself as an individual.

The alienation that we experience as students isn’t just a “personal issue”; it’s a consequence of our overbearing social structures. We live in a capitalist society that doesn’t value work or its workers — only profit matters, not the specific products that generate profit or the individuals who make these products. Alienation is inherent to capitalism because it is an economic system based on a division of labor where a small ridiculously rich minority controls the means of production. Because workers do not control the means of production — the complex division of labor makes them responsible for a specialized step of production — work becomes a monotonous, unfulfilling but vital means of survival. This process alienates workers because they are estranged from the products they create and the enormous profits generated from their labor.

Capitalist work ethic also prevents people from engaging with their ability to freely pursue creative endeavors. Work doesn’t necessarily have to be so meaningless that it is devoid of enjoyment. Work can be creative and tied to self-reflection and self-expression, contributing to the fulfillment of life rather than existing as its antithesis. The capacity to generate new ideas and create is what distinguishes humans as a species, but this capacity is not always valued as a productive use of time and energy.

Work is something we must do to survive in our society, and, if you’re privileged or lucky enough, you may enjoy it or have your efforts directed towards a purpose beyond your individual labor. Humans have a psychological need to feel that their lives have meaning, but this need is not met in a culture where work dominates the majority of our lifetimes. A Gallup survey in 2011-2012 found that only 13 percent of people worldwide actually feel engaged and look forward to their paid work, while 24 percent are actively disengaged and despise their work.

One of the main reasons so many people do not find meaning in their work is because they lack control of it. In the Whitehall study, Michael Marmot examined the stress levels of British civil servants and found that — even though higher-ranking employees had more “responsibility” — the lower-ranking workers had higher stress levels and greater risk of heart attacks. Lower-ranking workers in a capitalist economic system face greater stress levels because their low wages are often not enough to cover basic living expenses. Low-wage workers oftentimes have to supplement their income with additional jobs that require equally grueling labor conditions and long hours, taking away valuable time that could instead be used to rest or spend time with their families. Since the 1970s, there is evidence that there are direct consequences of working without autonomy or meaning, but our relentless economic system continues pushing for greater control over an increasing level of productivity.

In recent decades, the average number of hours Americans spend working has continued to increase as overall productivity exponentially rises. However, an escalation in productivity and innovation has not reflected a rise in overall quality of life for workers. Capitalist ideology dictates that production is geared towards profit, and while these products and technological innovations seem to “improve” quality of life, this is only a byproduct of the products’ ability to sell. As sociologist Juliet Schor notes in “The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure,” rising workloads lead to high stress — which 30 percent of adults report they experience at least once a week — and many other health problems such as depression, hypertension, and heart disease.

Similar to aspects of “professional” labor, college coursework often lacks encouragement of creativity and self-expression. This is especially the case for the many students who are devoting their time and skills to subjects that will provide financial security, or, in other words, subjects geared toward generating a workforce. Furthermore, students who have the privilege to study subjects they are passionate about can also find their passion crushed by the rigorous academic structure that breeds scholarly competition.

For instance, have you ever taken a genuinely enlightening class that challenges or validates your pre-existing worldview, but failed to realize how meaningful the content is because it’s associated with required readings and stressful deadlines? Learning is most effective when collaborative, and education should require encountering different perspectives that contradict, complicate, and expand your knowledge of the world.

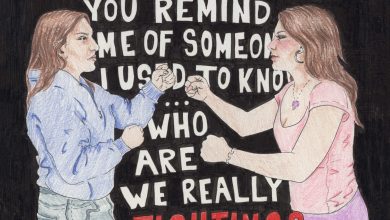

However, I often feel an irritatingly persistent need to compare myself to my peers — to be sure that I’m not completely falling behind in my career and academic trajectories. I regularly feel like I’m already behind in the “larger scheme” of life because I’m still struggling to determine what I want to make out of the distant future, while other people my age seem to have their entire lives planned out, as we are often expected to do. In reality, many college students face this extreme anxiety, but academic competition is nevertheless pushed to the extreme by the periodization of standardized markers of “success” that constitute “good” grades and high GPAs. These strict markers in education align with capitalist ideology which determines that humans are commodities themselves that have varying degrees of skills and competencies that determine the value of their labor and productivity.

The isolation we often experience in college stems from a greater commonplace alienation produced by the structures of capitalist society and economy. A lack of control and creativity characterize labor under capitalism, and there are direct physical and emotional consequences from this sustained lack of fulfillment. If we want to change the way labor functions in our society, we must engage in collaborative efforts to envision new ways of learning that encourage, rather than stunt, our collective intellectual growth.