Women Online Are Content

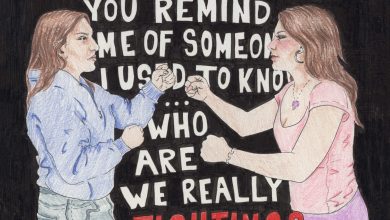

Image by Eve Anderson.

Praised be Pinterest, vanguard of the thumbnail feminist revolution, sanctuary for suburban moms with cooking blogs who are shattering the digital ceiling imposed by archaic advertising firms that thought they knew What Women Want. Bless the @realgirl, influencer not of lifestyles but of epistemologies, her selfie a practice of aesthetic empowerment and her feed a testament to post-identity womanhood. Everywhere we see cyborg women, Haraway’s supposed legacies, hacking away at gender essentialism with clicks as their weapon of choice.

In a talk titled “Social Media and the End of Gender” given at TEDWomen 2010, USC media researcher Johanna Blakley presented the thesis that social media, turning as it does on the data economy, allows us to escape the demographic boxes constructed by media companies on the basis of old-school stereotype. As the primary users of social media platforms, women would be “responsible for driving a stake through the heart of cheesy genre categories like the ‘chick flick.’” By simply using the Internet and feeding its voracious algorithms, Blakley suggests, women have the capacity to destabilize the corporate media establishment’s very center of balance.

Taken at face value, Blakley’s theory doesn’t seem to stray far from the lineage of cyberfeminist thought that envisioned the fledgling internet as a radical playground for gender reconstruction. A seminal text in this canon is Donna Haraway’s 1985 “A Cyborg Manifesto,” a critique of feminisms that rely on a totalizing definition of women as a homogenous class. As a “fiction mapping our social and bodily reality,” the political myth of the cyborg exists outside universality and primordial innocence, consequently disclosing “an intimate experience of boundaries, their construction and deconstruction.” Haraway regards the boundary-blurring properties of technological mediation as a promising frontier in our understanding of gender. A “cyborg theory of wholes and parts” reveals the labor of identity construction and the precarity of the physical, making the binary gender essentialism that imagined “woman” as a cohesive category of meaning obsolete.

Haraway’s definition of feminism as a politic of diffusion and deconstruction, a rejection of universalized political identities and embrace of networked affinities, bears a superficial resemblance to Blakley’s argument. That is, the malleability of the virtual can facilitate heterogeneity among women, thereby revealing that the emperor of “womanhood” has no clothes.

Crucially, however, Blakley borrows this belief in the potentiality of technology without its necessary counterpart — the tools we are talking about are quintessentially patriarchal, fundamentally shaped by what Haraway calls our “phallogocentric origin stories.”

This is where the two arguments diverge radically: Blakley’s hypothesis ignores the Internet’s nature as a tool for reinforcing the same stale misogynistic stereotypes, but in a way that is ever more impossible to detect as the digital threads seamlessly into our lives. Haraway presents us with the task of reconfiguring feminism in the language of advancements in science and technology, which always already shape our social and embodied reality. It is apparent that this is a language Blakley does not speak.

Blakley’s miscalculation is evident in the fact that technology, particularly social media platforms, has not dismantled the constraints and tyrannies of identity so much as it has replaced their raw material. To illustrate, in Rina Nkulu’s treatise on Glossier, the “first digital beauty brand,” she draws a clean parallel between the increasingly intangible nature of technology and Glossier’s “barely-there” approach to makeup branding. The company belabors the point that its products are “inspired by the people who use them” and “optimized for real life,” which in practice means they’re like any other commercial makeup product, but foregrounded by various shades of millennial pink. “Makeup is a choice,” the Glossier website declares, next to a photo of a woman’s full magenta lips that could be mistaken out of context for erotica.

There is nothing innovative about this pioneering digital makeup brand other than its fixation on the thin digital interface between simulation and reality. Nobody is buying the “real girl” bullshit in the age of VSCO editing, but no one likes a selfie that looks artificial either, and Glossier monetizes our balancing act on this familiar beauty bridge. Glossier is the cosmetic equivalent of posting ironically on social media, the chill and nonchalant shimmer of digital beauty obscuring the labor required to curate the look. It cannot escape mention that this look is super freely chosen; it seems we’re supposed to believe that Glossier taps into a primordial garden of feminine inclinations, and poreless Instagram brand ambassadors show up at their doorstep. The fetishization of the feminine-natural is now mediated by the very technology that was supposed to kill it off, and no one seems to notice.

Racial identity, too, finds new, shadowy homes in the alleyways of the Internet. In “Poor Meme, Rich Meme,” Aria Dean argues that internet memes transpose and extend the meaning of Blackness. The Internet is itself an ideal medium for Blackness insofar as it is “always already a networked culture and always already dematerialized,” characterized by dispersal and circulation and the double-consciousness of performance — seeds sown by the African diaspora and the violence of the Middle Passage. Given the free-for-all nature of the Internet, memes are yet another avenue for Blackness to be appropriated, mined, and consumed for entertainment value (see: digital blackface, or the use of Black bodies for online expression via meme or GIF). If the claim that memes are a channel for the exploitation of Black creative labor sounds vaguely absurd to some, we can attribute this confusion to the borderless, opaque terrain of the Web, which relies on infinite collaboration as its lifeblood. We are less post-identity and more what Nicolas Bourriaud called “post-productive” — beyond the limits of traditional ownership and embodiment.

In a sense, then, the meme enacts Haraway’s dream of a post-identity subjectivity, reminding us there is “no essential blackness, because blackness’s only home is in its circulating representations.” Dean also notes that “when society shines a light on it, what is atomized and multiplicitous hardens into the Black.” In calibrating targeted ads, it’s true that Facebook doesn’t ask for your race. But it does collect information that allows it to infer your “multicultural affinity.” Like frenzied memes, social network activities conceal race in digital code. Social media does not eliminate the stereotypes that ride on the coattails of racial identity; it scatters and submerges and obscures them until we hold them up to the light.

If the meme is Black, then perhaps it is also a girl. I say girl rather than woman because a meme is amusing and adjacent to cuteness, an aesthetic mode that Sianne Ngai theorizes as an infantilizing “way of aestheticizing powerlessness.” Memes are always already evolving, begging to be loved and go viral, never receiving attribution or recognition except as a youth culture novelty.

Girlhood has always been elastic, stretching to capture the ethos and anxieties of a nation (see: Shirley Temple movies as a repository for Great Depression suffering, or the contemporary existence of the not-at-all-satirical Teen Boss magazine for pubescent girl entrepreneurs). We now have Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, and Rashida Tlaib, who exist online not as congresswomen with actual policy platforms but as content-women, fetishized vessels of a post-Trump fever dream of liberal progress. Omar showing AOC her cute new Congressional Black Caucus jacket! Tlaib wearing a traditional Palestinian thobe at her swearing in! AOC dancing like a @realgirl from the Bronx!

In a paradoxical turn, the very fact of being online makes these congresswomen real. They are authentic and cool in the way Glossier desperately wants to be, although the brand of girl power being repackaged and resold here is political rather than a visual aesthetic. The patriarchy rears its head in the market once again, this time not as the determinant of what women really want but the antithesis of it. AOC isn’t like the other politicians, Glossier isn’t like the other beauty brands, and the Internet doesn’t exploit womanhood for consumption like the other ad companies — right, Blakley?

If there is a stake through someone’s heart, it isn’t gender’s. More likely, it’s the heart of our ability to recognize the way power infrastructures, now digitally enhanced, are capable of rearranging and manufacturing What Women Want. The revolution, unfortunately, will not be Instagram-storied. But with guidance from Haraway, Insta can help us find our torchbearer — not the real girl, but a monstrous cyborg.